Couldn’t we just get rid of homework? Basically no one likes it. And students get plenty of practice at school (or at least they should). The homework experience can go wrong in so many ways. Who needs it?

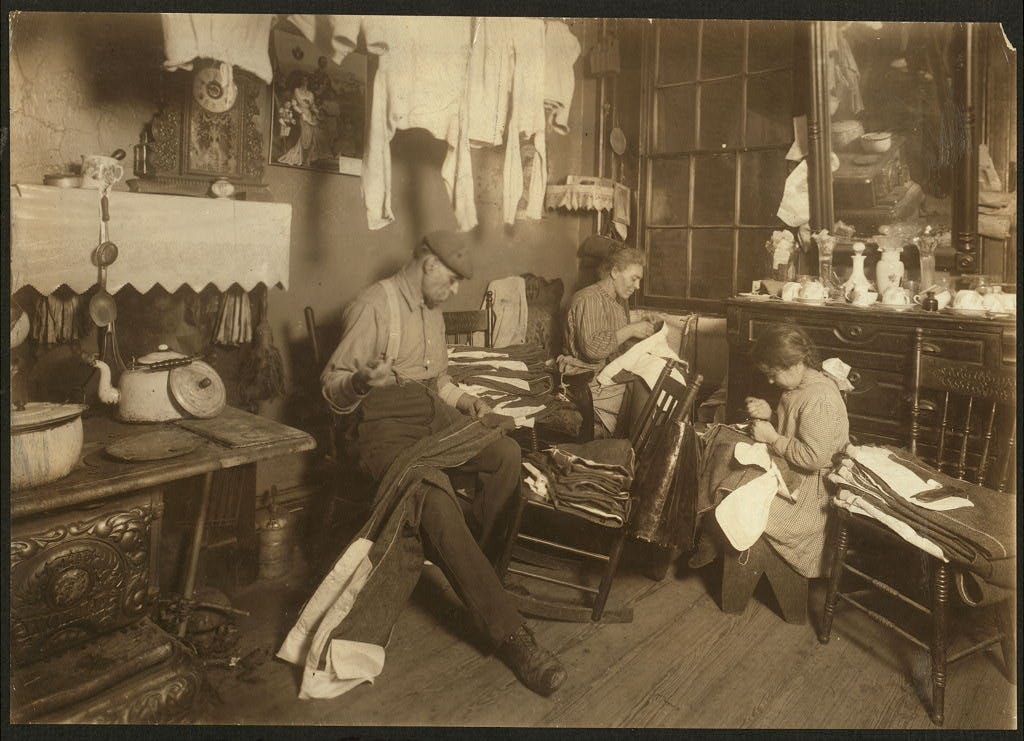

The first decades of the 20th century actually did see widespread agitation in the United States to eliminate homework. It came from educators and reformers who saw homework as an unfair burden on children and the home as a poor environment for learning.

The largest victory of this movement came in 1901, when the State of California passed an anti-homework law: “no pupil under the age of fifteen years in any grammar or primary school shall be required to do any home study.” Brian Gill and Steven Schlossman called this movement the “anti-homework crusade,” and it found victories in other districts and cities including Lynn, Massachusetts, and Washington DC.

This anti-homework movement was short-lived, though. Their problem was parents. In their article “Parents and the Politics of Homework,” Gill and Schlossman cite one frustrated crusader after another who ran up against a wall of parent opposition:

“In 1913, one principal who had abolished homework admitted that he “incurred considerable opposition on the part of parents, who were so indoctrinated with the idea of home study in their own school days that they protested vigorously against its prohibition” (quoted in Bok, 1913).

A fellow anti-homework warrior described the problem more succinctly: “I had to fight the parents: they felt that the pupils were not learning unless they carried home an armful of books every night” (Bok, 1913).

After the Washington, D.C. schools abolished homework below sixth grade, parents made “many urgent requests” for homework (Report of Board of Education, 1900–01, 1902).

Why is it that these parents were willing to fight for homework? I doubt that there was less stress at home in 1900 than there is today. But for many families, homework was – and is— about more than learning. It’s also about knowledge and accountability. Here are Gill and Schlossman again, on what motivated all those who defended homework from the crusaders:

Parents have few means by which to monitor the school and the progress of their children in the school. Homework gives parents direct knowledge (albeit inevitably incomplete) about the school’s educational agenda and methods. It tells them what the school is doing … Homework, in short, is a rare and valuable mechanism of school accountability to parents.

Homework isn’t just practice. For many families, homework is access, and that access is empowering.

So it’s not quite true to say that no one likes homework. Still, is it worth it?

What research says about homework

“Does homework improve learning” is a question that research has tried, and at times struggled, to answer. Writing in 2015, one group of researchers conceded that past work tends to show homework improving academic growth. But, they wrote, “when this effect is analyzed in detail there are inconsistent and in some cases contradictory results.” Not great!

One of the issues that researchers have to grapple with is how to measure homework. If we want to check whether homework impacts academic achievement, we have a choice: should we look at how often a teacher assigns it, or how often a student does it? On the one hand, it feels unfair to say that homework is ineffective if students don’t do it. Then again, that’s reality, and arguably a good homework assignment is one that students are able to complete.

Yet another issue is whether to measure how much time students spend on homework or whether students complete their homework. At first, some studies found a negative connection between time spent on homework and academic achievement. That was ultimately explained by pointing out that students tend to spend more time on homework when they are stuck or struggling with the material. Care is needed across the board when we’re designing homework research.

Fortunately, there are enough studies that take this challenge seriously that we can talk about a research-based picture of what homework can look like.

It’s fair to say that, according to the majority of good studies, homework probably does have benefits for students – though more for teens than for younger children. But that doesn’t mean the more homework, the better. Good assignments are meaningful and doable, and the benefits of homework might have a lot to do with fostering things like independence, ownership, and student agency. In other words, homework might be best seen as practice being a good student, as opposed to simply practice with one’s skills.

Let’s review this evidence, starting with the most basic question: how do we know that homework is worth it?

Does homework help students learn?

The short answer is, yes, homework does seem worth it, but with two major caveats. First, its impact isn’t as large or as clear in the research as some people might expect. Second, the impact for younger students is minimal.

There have been a truly enormous number of studies have looked at the connection between homework and academic achievement, making this a question of review and tallying. Much of this work was done by Harris Cooper, who did the hard work of identifying methodological flaws and sorting the wheat from the chaff.

What emerged when Cooper reviewed the research is a collection of studies, each with limitations, but collectively pointing in the positive direction for homework. And Cooper’s findings have been echoed by others:

“There was generally consistent evidence for a positive influence of homework on achievement.”

“Students in classes given well-chosen and challenging homework assignments learn more.”

“While each study that has looked at the link between homework and achievement has flaws, in general, they tend not to share the same flaws…I think it would not be imprudent, based on the evidence in hand, to conclude that doing homework can cause improved academic achievement.”

So, there does seem to be a case for assigning homework. But Cooper also found that the positive impact was moderated by the age of the students. In studies with younger children, there were much fewer academic benefits for homework:

"Still, this assertion must be quickly followed by the qualification that the positive effect of homework on achievement for young students may be limited."

That said, for younger students homework is almost universally assigned for the reasons stated above: it is an important part of the school-family relationship.

If a school wanted to entertain reducing or eliminating homework for younger students, it would be hard to argue from the evidence that this would impact their academics. But that school would need to think very hard about how they would replace that homework-sized hole for the families and caregivers of their students.

That said, teachers and families shouldn’t be concerned that the amount of homework their young child is getting is limiting their progress.

What does good homework look like?

Now that we know that homework has academic benefits, we might also want to know if we can get more benefits from assigning more homework. This idea shows up every now and again in the op-ed pages of newspapers: children simply need more practice at home!

If you’re a researcher trying to study this, though, you have some choices to make. The basic strategy is to see how academic achievement changes when you increase (or reduce) the amount of homework. But should you look at how long the assignments are or how often homework is assigned?

The same synthesis that appears above present an interesting finding: it appeared that the length of assignments doesn’t matter much for learning. But the frequency of assignments for older students made a much bigger difference. Homework, according to these studies, should be shorter but more frequent:

“The data point to the fact that the teacher regularly assigning homework matters more than the quantity.”

“Our research syntheses suggest that shorter but more frequent assignments are better than fewer long assignments.”

It’s not entirely clear from this research why shorter and more frequent assignments come out better. But I think there are two equally plausible possibilities.

It may very well be that many students are less motivated to do longer assignments. In fact, there is evidence that student perception that the assignment is challenging negatively impacts their motivation as well as the benefits of homework. Of course, the tricky thing is that what some students see as challenging, other students might think of as far too easy. But shorter assignments, presented more frequently, lower the stakes of that decision. Each individual assignment is less challenging (because it’s shorter), and it’s not a huge time investment for students who find it easy.

“We found that challenging homework assignments were negatively related to homework expectancy beliefs and homework effort and found differential effects for mathematics achievement. In our view, the complexity of our results reflects the difficulties teachers face in their daily routine: What is the ideal balance between cognitively activating instruction (i.e., challenging homework assignments) and instruction that caters for the low-achieving students in the class?

The other possibility, though, is that a value of homework for older students is that they have a chance to do academic work outside of the supportive classroom environment. This enables them to feel personally responsible for their learning and understanding, increasing their opportunities to learn both in and out of the classroom.

“Our data indicate that it is not necessary to assign huge quantities of homework, but it is important that assignment is systematic and regular, with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

If that second possibility is true, it might explain at least part of why homework has less of an impact on younger students. Those kids need adult help and structure anyway—they aren’t going to get much more independent about their academics yet, and they don’t need to, either. There will be time for that when they’re older.

How should parents help their children with homework?

Calm down, everybody—I’m not going to tell anybody what to do with their own children! Families and caregivers know their kids best.

Still, parents will sometimes ask me what sort of involvement or support I expect. And research is beginning to paint a picture about the risks of stressful conflicts surrounding homework. A recent study found that when parents report that their math homework interactions at home are negative, that can help predict how motivated and successful their children a year later, even when controlling for their current motivation and achievement. Could their be a causal link?

Another study, while looking at a large international dataset, identified a correlation between how frequently mathematics is assigned and the prevalence of math anxiety. In other words, when parents and children find homework stressful, there may be a lasting impact on the child’s relationship to and success with their academic work.

“The current research revealed that during early elementary school, parents’ involvement in children’s math homework tends to be affectively less positive and more negative than their involvement in children’s math activities.” (e.g. number games, flashcards)”

“The more affectively negative parents’ involvement, particularly in homework, the poorer children’s later math motivation and achievement.”

“Interestingly, our results suggest that homework may play a significant role in math anxiety. We found that the frequency of homework assigned is related with higher math anxiety, which is consistent with previous findings (44, 51). Similarly, we also found evidence to suggest that parental involvement with homework is associated with an increase in math anxiety, which again is in line with previous findings (55). These findings suggest that homework and the degree to which parents are involved in their children’s homework must be considered carefully in any future study of math anxiety as well as potential interventions to alleviate math anxiety.”

The message for parents, in my opinion, is that your first job is to make sure homework is as calm and positive an experience as is possible. Everything else, as far as I’m concerned, is optional. Parents can help or not, depending on what they feel is best. As long as everyone is feeling good.

In the first of these studies, parents reported fewer negative feelings when the homework assignment was to practice with flashcards or to play a math game. This might be because the student is self-sufficient in these activities. Maybe it’s because the assignment is more pleasant for everyone involved. But it raises a possibility: could teachers assign homework that avoids tension?

Some researchers have tried to create different types of homework that help guide adults towards constructive, positive interactions. In “interactive homework,” Joyce Epstein and Frances Van Voorhis created assignments that involved the adults at home without making them responsible for guiding practice work. They asked students to do things like conduct family surveys, share an explanation the teacher presented at school, have a conversation with someone at home about a topic, or ask parents when they use a certain skill in their lives.

“Interactive homework” encourages students to share interesting things they are learning in class with family members, friends, peers, or others in the community (Epstein, 2001). The Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) process is one design for interactive homework that guides students to conduct conversations and interactions with family partners in math, science, language arts, or other subjects (Epstein et al., 1995).”

Speaking as a classroom teacher, these seem like a lot of work to put together. I also know that some parents would want more conventional practice, so they could see what their children are learning and how well they’re performing. Still, “interactive homework” is a nice idea and I try to make sure that it’s part of my homework mix.

What I Do

I personally dislike putting together homework assignments. If I have ten minutes, those ten minutes are usually better spent improving part of my lesson rather than making some new worksheet to send home as an assignment.

I also don’t like collecting homework. Do I devote class time to go over it? I could, though the students who got the answers easily might be bored. Do I give written feedback on it? I could, though that feedback rarely seems to help anyone’s learning.

For these reasons and more, digital homework is the best thing technology has done for my teaching in the past decade.

It’s not because digital homework is more effective or more motivating than typical homework (though it might be). No, it’s because digital homework is easier for me. It’s quicker to assign and it marks itself automatically. I don’t have to go over it in class (though I can) and there is no turning in or handing back. For older students in my math classes, it’s close to my ideal.

(It’s not an option for my 3rd or 4th Graders!)

My preferred program is Deltamath. It’s dead simple in the best ways – if a student doesn’t know how to complete a question, they can click a button to see a worked-out example. Answers are given right away, I can easily check to see how successful the class was with their practice on a skill. I can even print out new questions on the same topic, to review the homework in class the next day.

That said, I’ve noticed that kids get annoyed if I overdo the digital homework. So my actual approach aims for balance. Here’s what I do:

I assign homework three times a week.

For younger students, these are relatively quick review assignments. I try to include optional challenges with the homework. I tell families that if their child is finding the homework “too easy” then they should be working on the optional challenges. All the assignments are on paper. Sometimes I’ll send home flashcards to practice with (but I’ll always end up losing some in the shuffle).

For older students, I assign one or two Deltamath assignments a week. The first is over the weekend—the ideal time for digital, since they get quick feedback even though they might do it on Friday afternoon and not see me until Monday. Also things tend to get lost over the weekend, but this doesn’t need to be handed in.

At the start of the week, for variety, I’ll make sure there’s a paper assignment, for variety’s sake. This will also be review. Their next assignment will be either paper or Deltamath, it depends on how I’m feeling and if I’ve got something handy nearby to photocopy.

The assignments are all relatively brief, a handful of questions.

The assignments are always review.

Why review? It provides purpose to the assignments and solves a bunch of problems. I can’t explain this much better than Henri Picciotto does in his writing about “lagging homework”:

Lagging homework extends students’ exposure to the ideas: what could (with perfect students) be done in one week now takes two weeks, which gives the students who need it more time to absorb the ideas. And this without harming the students who don’t need the extra time. In fact, it gives them an opportunity to later review ideas that they may have absorbed too fast.

That’s how I try to make sure my homework makes sense to families, stays manageable for me, and gives a chance for my older students to step up to take responsibility for their learning.

Main takeaways

Homework has been found to have some academic benefits for older students, and significantly fewer benefits for elementary-age students.

Shorter, more frequent assignments have benefits to students—perhaps because they are more doable, and perhaps because they foster a student’s sense of efficacy, independence, and responsibility for their own success.

Homework is often stressful and negative for elementary age students, and those experiences might be related to future academic outcomes. Homework should be designed to minimize stress and negativity to whatever extent is possible.

I thought the findings from the study were illuminating, and agree -- I think the dynamic they discuss is quite real. It made me wonder both about practical considerations for how to assign homework but also about educator PD and learning. i.e. what conditions would need to exist for a teacher team to have a real conversation about how something like this might be playing out in their classrooms and what they might do about it.

I emailed you. See further:

1. https://3starlearningexperiences.wordpress.com/2016/04/19/make-sense-not-war-suggestions-on-how-to-make-homework-more-effective/

2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303779377_Homework_and_Achievement_Using_Smartpen_Technology_to_Find_the_Connection -

I wrote a blog about this (in Dutch) but translating it should be simple in Chrome (right click, present in English) or Deep-L: https://onderzoekonderwijs.net/2016/07/06/onderzoek-naar-huiswerk-toont-belangrijke-beperkingen-vorige-onderzoeken/

Paul