The most popular book in mathematics education right now is Building Thinking Classrooms. It currently has 1682 ratings on Amazon, which feels like a lot, though not quite as much as Jo Boaler’s Mathematical Mindsets which has 1791. I have no idea if this is a good stand-in for a book’s popularity. But Carol Dweck’s huge bestseller Mindset has a whopping 21,667 ratings. (My own edu-book weighs in at a respectable 78.)

What makes these books so popular? One thing they do—I think it might be a characteristic of all world-beating ideas—is combine a big, explanatory theory with a few handy techniques that anybody can try.

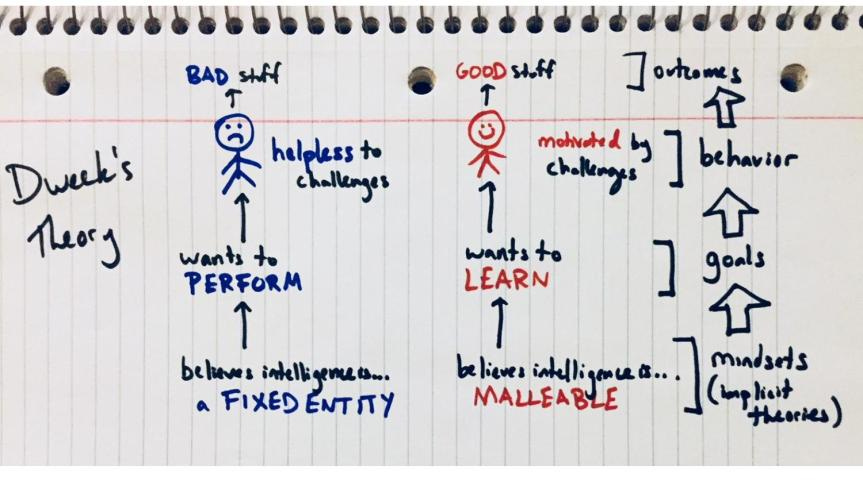

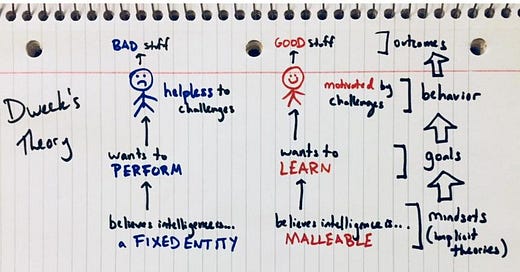

Take Mindset. It posits that people with similar skills are differently motivated. For Dweck this flows from one’s theory of intelligence. You either have a growth or fixed mindset. A growth mindset is a tendency to explain failure in terms of things you, the individual, can control. The tendency orients the individual towards learning goals. The result is that challenges, seen as an opportunity to learn, are motivating. Whatever. My point is that this is a theory, and teachers (along with the media, bosses, parents) loved it.

But it wasn’t just theory. Mindset only got huge when people learned that the theory generated some simple, distinctive actions:

Don’t praise someone for “being smart.” Praise them for working hard.

Motivate people by telling them about the brain’s ability to grow.

Without theory this practical stuff would feel inert. (What if Dweck had given a TED talk called “10 Motivation Hacks”?) Combine theory with practice, though, and it’s magic. The easy stuff stands in for the entire set of mindset ideas, and are imbued with this tremendous shiny meaningful energy.

When you praise your kids correctly, you are doing mindset. Or, at least, that’s how it can feel. Of course you’re not really doing it all. You’re just doing the easy stuff! But it might feel as if you’re thereby making some radical and comprehensive change by praising students for their efforts—even if, say, your classroom is structured in a way that makes it difficult to learn and grow.

Peter Liljedahl’s comparatively modest hit Building Thinking Classrooms follows a similar playbook. I doubt that this was intentional, but it’s perfectly engineered for popularity.

BTC has a theory as to why students aren’t learning. “Thinking is a necessary precursor to learning, and if students are not thinking, they are not learning,” he writes. So what are kids doing in school, if not thinking? Skating by with false engagement (“studenting”).

The BTC approach aims to break this culture of “studenting.” It’s sort of a shock-and-awe shift meant to confront kids with a radically different set of classroom expectations. Everything looks and sounds different in BTC: defronting, thin-slicing, notes-to-future-forgetful-selves, mobilizing knowledge, check-your-understanding questions (in place of homework), consolidating, and much more.

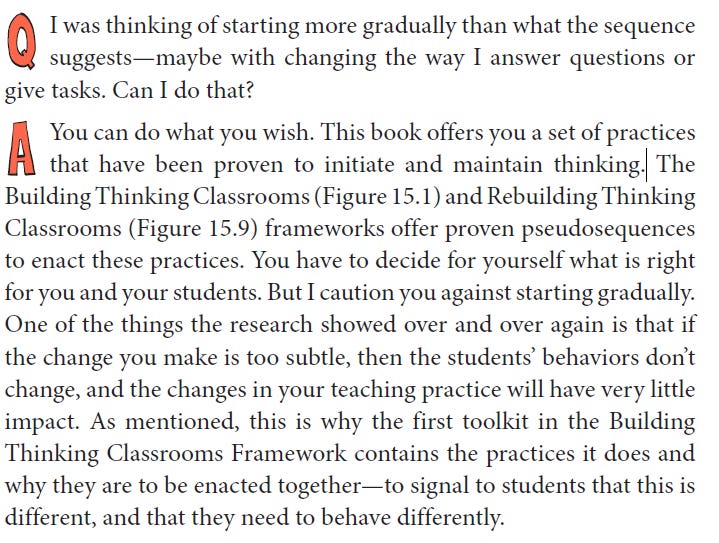

BTC strongly encourages teachers to take the whole plunge at once. The book emphasizes the need to do all this stuff together. (See excerpt below.)

But two BTC practices are by far the most popular among teachers:

Group work at vertical whiteboards (or as BTC calls them “vertical non-permanent surfaces”)

Assigning group partners randomly

Liljedahl could not be clearer that he is offering a comprehensive theory and radically different approach. But there are tons of teachers whose use of BTC extends to almost nothing beyond these two practices. Even if teachers are doing everything else exactly the same, they feel as if they are doing BTC if they have kids working at whiteboards in random groups. It’s the “praising effort” of Liljedahl’s approach.

“So what?” a lot of teachers say. “I take the parts that I like and don’t care about the rest. I’m pragmatic.” This is true—teachers (and everyone else) do this a lot.

But the irony is that you need to go big and comprehensive if you want your small practical ideas to spread. They need to be part of a theory, if only so that people can scrap the system for parts. We want our useful hacks to be part of something bigger.

***

At least in teaching, theories tend to fade, leaving behind the practices. David Tyack and Larry Cuban in Tinkering Toward Utopia called these “instructional add-ons.”1 The big radical ideas get digested by the teaching profession until all that’s left are those catnip practices. In thirty years, BTC will be unknown, but there will still be schools that swear by vertical non-permanent surfaces. It’s just how it goes.

You can see it happening now. In online support groups for BTC practitioners, teachers ask for help enacting the system’s somewhat demanding aspects. They may cheat a bit and offer explanations at the start of the lesson (not allowed in BTC). Or they may be unsure how to “thin-slice,” which is the BTC-approved method for learning new skills. After well-intentioned efforts to make the whole thing work, most people will end up delivering entirely conventional math lessons, just with whiteboards.

But take a moment and admire the power of theories.

Teaching (or parenting, or bossing, or social-working, etc) is confusing work. There are days when you think you’ve figured it out, only to run into humiliating defeat. At it’s worst it feels random, chaotic, and unpredictable. Well, sure. People are random, chaotic, and unpredictable. Anyone who works with humans either routinely struggles with this, or is not paying enough attention.2

We need theories to help make sense of this mess. We want labels and categories and explanations to help us make order out of the chaos. We want to understand our options and act more consistently. Of course, it also has to be practical. Nobody likes irrelevant ideas that can’t be easily brought into action.

Is this healthy? I don’t know. Maybe it is, and what we need are better books and systems. But look around at what resonates with people—there is a desperate, aching need for ideas, the bigger the better, and that’s not going to change any time soon at all. People absolutely love theories.

They were talking about technology that was supposed to fundamentally transform teaching. Same phenomenon, though.

Or you have some very nice humans to work with.

This is so well-said spot on: “The big radical ideas get digested by the teaching profession until all that’s left are those catnip practices. In thirty years, BTC will be unknown, but there will still be schools that swear by vertical non-permanent surfaces. It’s just how it goes.” So is it that teachers love theories or that the grand theoretical claim is what’s necessary for the practical hacks to get adopted?

We have a number of pathologies as a profession that get us into trouble over time. It's why you see so many ideas that are simply reframed, reworded or re-legislated ideas from previous decades. Of course, all that revision is often rolled into the discourse as a way of justifying the resurrection of these ideas. Partly that's a natural consequence of the way education works, but it is not necessary always beneficial :)

Earlier this week on twitter Ben Newmark made a point very similar to yours. He suggested that most educational books were a lot of padding and that the valuable ideas for a jobbing teacher are really only a blogpost long. I have sympathy for that viewpoint and I think it ties in to what you are saying. I also wonder if part of the issue is a mismatch behind why most people write edbooks and what teachers are capable of applying. Most authors have worked hard on developing an idea and all the mechanisms that go with it. Their new silver bullet needs to be implemented with complete fidelity and all these strategies and tips are connected. Problem is as a teacher we are not often in aa position to implement everything. Time gets in the way; administration gets in the way; lack of resources and competing priorities. So we jump at the mircro-strategies and stick them in. We have made it better, even if not completely, haven't we? And if it starts to work we are of course happy and so it becomes part of the repetoire. We probably get better and better at it, understand it more deeply, more intuitively and so are more comfortable with it. Then when somebody else later on says 'hold on, this is better' we naturally, and quite logically, dig our metaphorical heals in.

It's hard being a teacher, isn't it? Then why am I so pumped to start work next week?!