The SAT is not fairer than grades

Especially for poorer students

I.

Say that you are a relatively poor high school student living in the Bronx. You would like to attend the City University of New York. CUNY is a pretty good school—an especially high fraction of poorer students who attend CUNY end up moving into the top 20% of earners. You’d like to go there and do that.

The vast majority of schools are interested in both your grades and your SAT scores. But, increasingly, there is a movement to make SAT scores optional, and some colleges are announcing they won’t even consider the scores.

As a poorer student, would you rather have your application based on your high school GPA or your standardized test scores?

On average, there is a pretty clear answer: if you’re poor, you’re better off being judged on your grades.

This study looked at what the top applicants would look like in California if HSGPA or various standardized tests were used to judge merit. HSGPA resulted in a higher percentage of poorer students becoming top applicants.

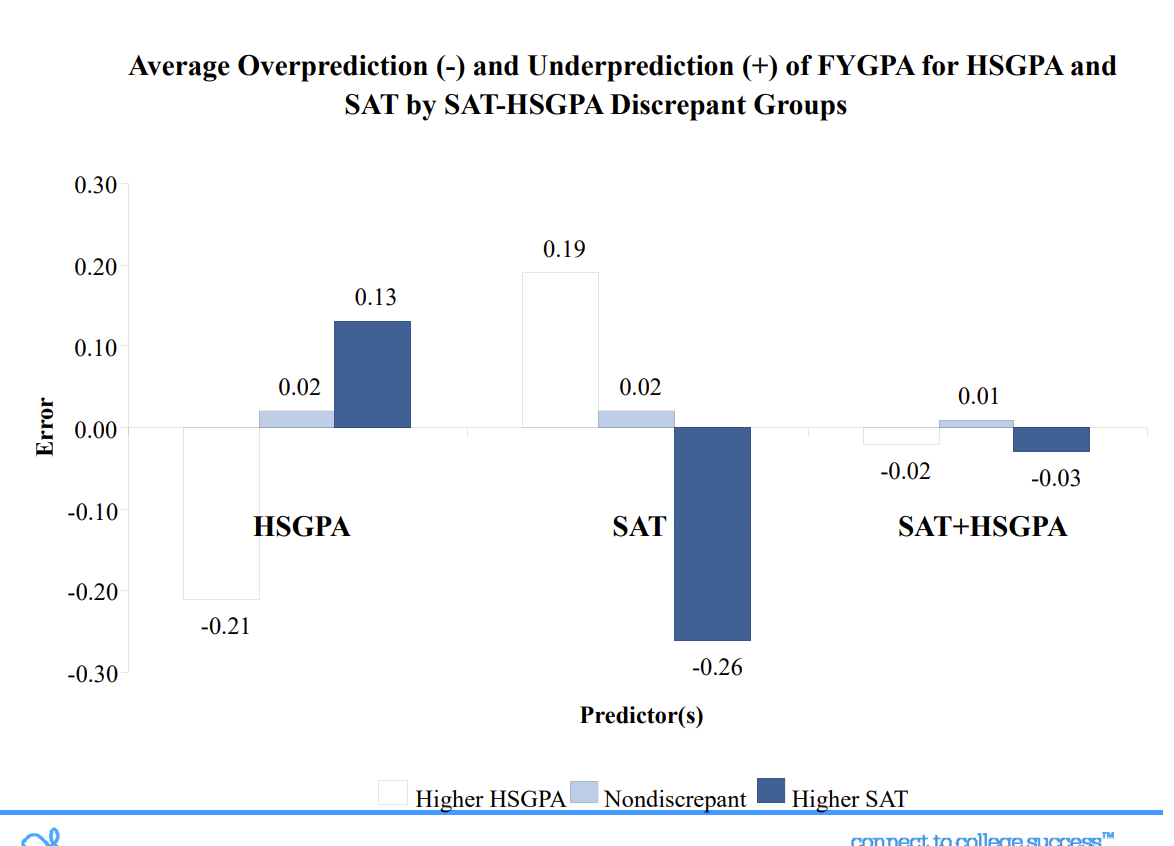

Researchers from The College Board, designers of the SAT, also studied this. They found that HSGPA and SAT correllated well about 2/3 of the time. 1/6 of the time, SAT was stronger than HSGPA scores. About 30% of those students had parents who made more than $100,000. And poorer and middle income students tended to have stronger grades than scores.

.Now, you might say that this is just because SAT is more accurate than HSGPA. Grades are just worse at measuring what we care about, and SAT is correct.

The conventional thing that people say in this context is that we are trying to predict who will thrive in our colleges—the logic being that top applicants are those destined to do well in the schools.

Arguably, that logic is stupid. Aren’t we supposed to be educating people, not making bets on their futures? But let’s go with it for now, because that same College Board study found that HSGPA on its own does a better job predicting future college performance than the SAT does on its own, with the best results coming from using both together.

OK, but maybe what we care about are advanced degrees? Rebecca Zwick (who likes SAT+HSGPA) writes about this in Who Gets In?:

“Perhaps the most interesting finding concerns the percentages of students who completed a postbaccalaureate credential by 2013, nine years after high school graduation. The vast majority of the credentials received were either master’s degrees or ‘professional doctorates,’ which included degrees in law, medicine, and dentistry.”

Grades are better than scores at predicting who ends up getting those degrees.

I don’t mean to go easy on grades. Grades are subjective. Effort, attendance, politeness, general classroom demeanor all affect them. Different teachers have different standards, even for the same essay and even with the same rubric. Many teachers are allowed to design their own personal systems and so in that sense grades are absolutely and without a doubt, inconsistent and unfair.

Wealth can change grades. There is grade inflation. There is pressure from influential (or just plain persistent) parents to get extra credit, retests, or just make the damn grade higher. There are tutors who help with homework and “help” write essays. Grades are patently unfair in favor of the wealthy—

And yet, all the above! Zwick, again:

“When we calculated the student-level correlations within high schools and then took the average, we found that the association with SES [socioeconomic status] ranged from .20 to .25 for SAT scores, from .12 to .18 for high school GPA, and from .15 to .21 for class rank.”

Grades are made up, but on average you’d rather be judged on them if you’re poor. And—even though they absolutely suck—grades are more accurate for making predictions about future academic outcomes.

How could this be?

II.

Well, standardized tests are also unfair in favor of the wealthy.

There is a certain kind of discourse about tests that drives me nuts. It doesn’t say, “standardized tests are flawed but valuable,” which is more or less what I think. No, it says that tests represent cruel objectivity, the harsh light on a student’s true academic potential (whatever that means).

Some kids have bad test scores and strong grades, these guys say. But those kids have teachers who are going soft on them. These are kids who won’t grow up to be smart genius bros. Because they aren’t really smart; they’re just good at school. If they were smart, they’d do well on the SAT.

OK, first of all, no, you’re talking about the wrong test.

The SAT Math section is an algebra test. You will do well on the SAT Math section if you thrived in your Algebra II class, and if your Algebra II class covered all the topics. The College Board, presumably channeling Joseph Conrad, says the test has a Heart of Algebra. Gotta know that algebra.

Do you know who teaches algebra? Schools do. And tutors do as well, if school isn’t enough, and if the family can afford it.

Critics of grades often point out (correctly) that schools have very different standards. An “A” in one place may mean something quite different from an “A” in another. True! But the exact same thing has an impact on test scores. Through no fault of their own, there may be a mismatch between a student’s education and the exam. Grades, on the other hand, reflect how well a student met their teacher’s expectations—though with higher expectations, maybe they’d ace the test.

This favors wealthier students, who tend to go to schools with expectations aligned to the exam.

But all this is dancing around the most significant point, which is the test is not intrinsically a better measure of learning than grades. That’s because it’s a single snapshot. It’s a big, bad exam. It’s high stakes. People have bad days! True, people also have bad years, but there is something unfair about making everything ride on a child’s performance on a single day.

Sure, the tests are designed well enough. What you get is more objectivity, but what you lose is information about the student’s history, and you open yourself up to the possibility that a child has an upset stomach, has to run to the bathroom, or gets very unlucky on a particular testing day. Grades are unfair, but tests have their own sources of unfairness.

Not to mention, by the way, that you score worse on standardized tests if your school doesn’t have air conditioning! Which is just a reminder that being wealthy doesn’t only buy you better grades—it also buys you better test conditions for your high stakes performance.

So, in short, yeah, grades suck, but so does the SAT. The SAT is just a standardized school test. It takes a single snapshot, and there is the potential for a mismatch between what a student learned in math class and what the test expects. The SAT is not an awful test, and it’s certainly more objective than grades, but objective doesn’t mean fair and the SAT is not more fair.

III.

I guess my vision of fairness is I like second chances. School doesn’t work well for everyone, and I don’t like the idea that your only path towards social mobility in this country is you have to do great in one school, so that you can go on to do great in some other school afterwards.

Ideally I’d want a path towards middle class respectability and comfort and healthcare (this is America) that doesn’t involve being a good student at all. But at the very least you should be allowed to mess up high school, have terrible grades, and still be able to get into a good school. You deserve a second chance. If the SAT can be that for some kids, great.

(I took that to be the main argument Erik Hoel made in his essay lamenting the decline of tests in admissions decisions.)

I mean—this is all crazy, though! What an insane way to dole out healthcare. What are we even doing!

I’m not going to argue that tests are worthless. If you’re a student born into povery, you need any advantage you can get in the system. It’s not like tests are not also stacked against you. On average they are more stacked against you. But why can’t they be a second way that you can show what you can do?

Sure: more wealthy students will take advantage of these second chances.

But that’s a question for a different moment. I’m thinking about a student who lives in my local neighborhood here in NYC, who goes to the local school, whose parents or grandparents were immigrants to this country, who wants to go to the local college, and we’re wondering if CUNY should judge students like her based on grades or standardized exams.

And my answer is, judge her on whichever is stronger. Just give her a chance.

Thanks for reading!

I’m awful at self-promotion but trying to get better! If you’d like to, consider subscribing.

And if you’d like to support my work you can buy my book:

Something interesting about grades, the Crescendo Education Group, the main consulting group that pushes for and trains teachers on equitable grading, claims that one of the signs that equitable grading is more fair is that it correlates more strongly to testing scores. (See https://crescendoedgroup.org/results/) It seems they're doing something weird to get these correlations, but I thought it was interesting.

I have always been opposed to standardized tests because they are particularly difficult for those with any type of learning difference. Especially those with dyslexia (which is approximately 1/5 the population regardless of language or culture). Wealthy LD children have a significant advantage because their disabilities are often caught early and they are given appropriate tools for learning.

Something to motivate any of your students who might be struggling with standardized tests: your cousin (who is a professor of Mathematics at an ivy league school) scored in the low 500s on his math SAT!!!