Though it’s rarely discussed in education, nobody knows how many students have a mathematical learning disability. It could be anywhere from 1.77 all the way up to 13.8%—it depends on which definitions you choose.

This is not some tremendous secret. The textbook Learning Disabilities is completely upfront about the field’s “persistent vagueness,” writing that “no consistent standards have been established by which to judge the presence or absence of LDs in math.” Researchers and many special educators certainly know this, even if it’s less than common knowledge among teachers, parents, and students. To understand how we ended up here, zip back to 1963 when a group of advocates told Samuel Kirk that they needed a word to describe their struggling children.1

Invention of “Learning Disabilities”

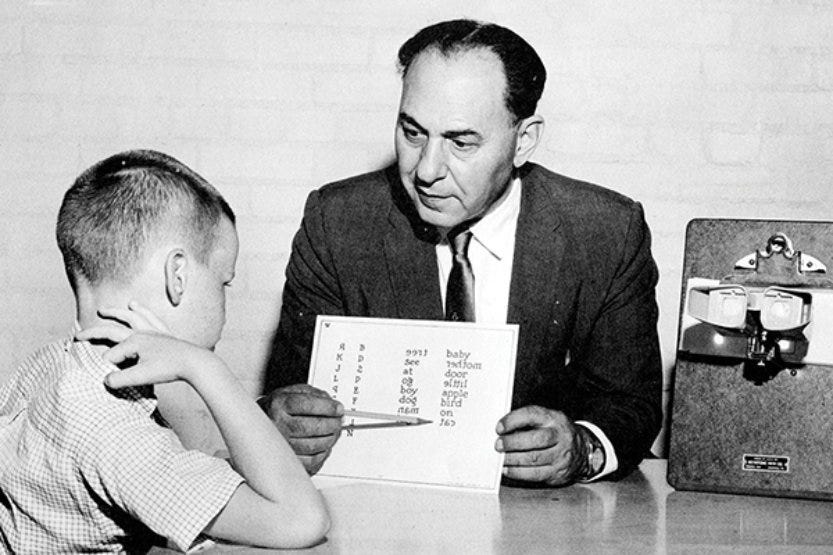

Kirk, born in 1904, had a self-styled reputation as a practical scholar. He liked to tell how, at age 25 while working in a residential home, he snuck reading lessons to a delinquent “word blind” boy after curfew. The boy, against diagnosis, successfully learned to read. Teaching supposedly uneducable students would become Kirk’s great quest.

By 1963 he was a leading researcher in special education and invited to speak to a group of parents. Earlier groups of parents had successfully lobbied the state to guarantee services to handicapped and “mentally retarded” children. But these parents had children who, though generally intelligent, were not progressing in reading and mathematics as they should. The parents had no idea what to talk about their kids’ issues—were they “brain-injured”? “perceptually handicapped”?

A friend tipped Kirk off that he’d be asked to supply some sort of label. So Kirk, in his address to the meeting, reluctantly shared a term he had started using to refer to students with unexpected learning troubles: they had a learning disability.

The parents named themselves The Association for Children with Learning Disabilities. Just six year later Congress would pass PL 91-230, guaranteeing services to students with “specific learning disabilities.”

Kirk, being a practical man, had long found definitions confusing and frustrating. In 1960 he told a colleague, “I think we are still struggling with terminology as we have been for the last fifty years in this field.” He didn’t love labels either. “I have felt for some time that labels we give to children are satisfying to us but of little help to the child himself.” He told this to the parent group immediately before introducing his new term.

In The Incomplete Child, Scot Danforth offers a tidy chart tracking 16 different versions of his definition that Kirk used between 1960 and 1984. He added and subtracted components over time. He did his best, but the truth is that Kirk didn’t care. He just wanted to teach children to read.

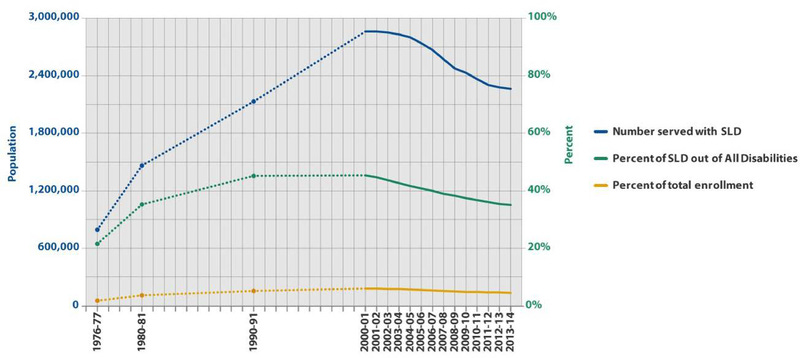

Meanwhile, learning disability diagnoses exploded in the wake of the 1969 law.

A Popular Diagnosis

The core of the learning disability concept is a gap between potential and performance. If you aren’t intelligent, you don’t have a learning disability—you’re “mentally retarded.” Every LD diagnosis is then a kind of compliment to the child, even a promise. The child is intelligent. With help, they can learn.2

The definition that made it into the federal law was not technical enough to guide diagnosis, so in 1976 the US Office of Education said the mark of LD was a “severe discrepancy between achievement and intellectual ability.” This was almost universally interpreted as a gap between IQ and achievement on some other standardized test.

The situation continued to deteriorate. A 1985 Education Week headline reported, “Steady Rise in Learning-Disabled Spurs Review”:

Many believe the learning-disabled classification has become “a dumping ground,” according to Anne Flemming, president of the Association for Children and Adults with Learning Disabilities. Educators too often say, “‘If a child misbehaves, we’ll send him into a learning-disabled class,”’ Ms. Flemming said.

Meanwhile, the research establishment firmly turned against the use of IQ-achievement discrepancy. Why should two students with equal mathematical ability get different services, only because one scored higher on an IQ test? Was a single IQ test valid to determine potential, anyway? Besides, an IQ-achievement gap wasn’t itself supposed to be diagnostic unless other explanations (like motivation or home environment) were considered. You weren’t supposed to be labeled with a learning disability for being a recent immigrant. But that’s what was happening.

Can Interventions Save the Day?

In 2004, US Congress reauthorized IDEA, the law guaranteeing special education services, and for the first time offered a clear alternative to IQ-achievement discrepancy. This was the introduction of RTI, or “response to intervention,” offering a totally different way to think about learning disabilities that I think Samuel Kirk would have absolutely loved.

RTI said, listen, there is such a thing as research-validated instruction—interventions that have been proven to work for a wide variety of struggling children. So let’s use that for identification. If we offer a kid a small-group intervention that has been already shown to work, and it doesn’t work? That may very well indicate that they have a learning disability. It’s a teaching-first way of identifying kids for special services, and I personally think it’s very clever.

If you’re keeping score, this leaves us with three significantly different approaches for identifying LD:

Exclusionary definition — if a kid is struggling with reading/math and there’s no other good explanation for why, they have an LD. (Or you could say a “specific learning disorder.”)

IQ-achievement gap — if a kid is underperforming what you’d expect from their IQ test, and there’s no good explanation for why, they have an LD.

Response to intervention — if a kid recieves research-validated instruction and it doesn’t work, and there’s no good explanation for why, they have an LD.

The RTI approach, however, puts the burden on schools and how interventions work in practice. Oh, terrific. A 2015 study found looked at 20,000 first-graders who had been targeted for RTI. And how did that go?:

“First graders who received reading interventions actually did worse than virtually identical peers who did not get the more targeted assistance.”

And this, more or less, is where things stand today. Ask a teacher how RTI works at their school—they’ll scrunch up their face while simultaneously sighing. In most places the system isn’t working as intended. It remains a mess.3

Last year Education Week published a little explainer about learning disabilities. “Dyscalculia, a severe, persistent learning disability in mathematics,” they wrote, “affects about 5 percent to 8 percent of school-age children nationwide.” If only it were so clear.

Kirk approached his work as a special educator with a strong dose of pragmatism and subjectivity. But the federal government doesn’t work that way. Education doesn’t work that way either—there are rules, laws, definitions, and a need for equal treatment under the law.

It turns out that objectivity is also fairly popular. Diagnosis can be a true relief for parents and children. But when a student has a mathematical learning disability, what are we diagnosing them with?

“Unexplained underachievement” remains the core of the learning disability concept. The explanation is in a sense the lack of explanation itself. It’s a funny concept (I find it funny) that points to a real group of students that deserve attention and support.

I am no longer surprised that there’s so much disagreement about how prevalant dyscalculia is. And neither are the researchers and teachers who continue to search for ways to help struggling students. In an important sense, prevalance just doesn’t matter—the labels we give children might be satisfying to us, but often little help to children themselves.

Don’t read this footnote unless you’re already angry at me. OK, most of you are gone? Yes, I have elided the difference between dyscalculia and mathematical learning disability (MLD). Dyscalculia is possibly a specific kind of MLD. That’s a whole other essay, untangling those terms. OK? And I’m also going to elide the difference between “learning disability” and “specific learning disability” too because SLD is a real mouthful. I’m sorry about this. Don’t be angry.

But is this interpretation correct? Kirk waffled as to whether students with more severe generalized disabilities could also have a more specific one. If a student is not living up to their potential as a reader, whatever that potential may be, couldn’t that be a learning disability? Untangling the “comorbidities” is an ongoing project, and a humongous mess.

Oh, we’ve expanded RTI and reconcieved it as some other more general school support system called MTSS, multi-tiered system of support? But WHY???

Great piece.

Great stuff as usual. Is there anything we diagnose well, outside of medical issues with clear biological markers? For example, you could have written this essay about ADHD.