Practice Software is Struggling

Why whole-group teaching is easier than individual practice

Hello!

I have a humor piece in McSweeney’s that you should check out. It’s about a guy who uses AI to write his wedding vows. Some people think it’s funny! I also want to remind you of the story about Renaissance math duels that I posted here a few weeks ago. Please read, share, and enjoy.

Holly Korbey has a good article in Education Next about how math practice software kind of sucks and everybody hates it. I’m summarizing. But she names names. We’re talking Dreambox, Zearn, i-Ready, Khan Academy, ALEKS, and IXL.

The big issue is what is sometimes called the “5 percent problem.” This is the observation that these programs work fine when used as intended but are rarely “used as intended.” Instead kids cheat, copy, click around, get bored, switch tabs, flirt, swap computers, or walk away. (5% of the time, IXL works every time.) It’s a big issue, but the industry is working on it. Just wait, you’ll see. Soon enough we’ll be talking about a 6 percent problem, or even 7.

I tease. But the situation for these companies isn’t great. Lots of users (not all!) dislike their product. Per Korbey’s article:

“Teachers hate it and students are lost,” said one Texas math teacher.

“The kids were screenshotting, taking pictures, and just rapidly going through the questions, and then they would go through it a second time, get 100 percent—they got their points—and move on to the next thing… It was pure chaos, and students weren’t getting anything out of it.”

Kane said he “hasn’t touched” the ALEKS digital platform his school purchased and favors designing his own practice problems.

Hey, wait a second—that’s our buddy Dylan Kane! Nice. Later in the article, after trashing ALEKS, Dylan shows up with a recommendation: “Kane, the 7th-grade teacher from Colorado, has found his own digital solution, similar to ASSISTments—DeltaMath.”

Now, I like Deltamath and my students do too. But, like Dylan says, it’s not personalization software. There is no algorithm. It is not adaptive. It does not aim to teach students topics they don’t yet know. It offers no incentives or rewards. It is not the future of education. It will not eliminate the need for teachers. (Listen, I’m disappointed too.)

This is where I’m supposed to say something like, “personalized tutors would be nice, too bad the software isn’t there yet.” But I don’t buy personal tutors as an ideal. The dream of a digital tutor is it gives you precisely what you need to learn at a given moment. I don’t believe in “precisely.” I think there are a lot of things you’re ready to learn at any given time, and beyond a point it doesn’t really matter what you study.

I also think there can be returns to learning with your classmates—what’s called peer effects.1 There is a fun historical example of this. As detailed in “Masters of Theory,” the top competitive math coaches at Cambridge University in the 19th Century — guys like William Hopkins and Edward Routh — taught groups of students, not individuals:

“Unlike the majority of private tutors, [Hopkins] taught students in small classes–between ten and fifteen pupils–composed of men of roughly equal ability. This meant that the class could move ahead at the fast possible pace, the students learning from and competing against each other.”

“The primary method of teaching, around which Routh’s whole system was built, was the one-hour lecture to a class of not more than ten pupils using blackboard and chalk.”

These guys weren’t simply working with groups out of necessity. They chose to work this way for the sake of their students. Like them, I also find teaching to be at its most satisfying and productive when the entire class is pointed at the same target. Part of what I love about Deltamath is how I can make it help me with whole-group learning, even though that’s not really what it was built for.

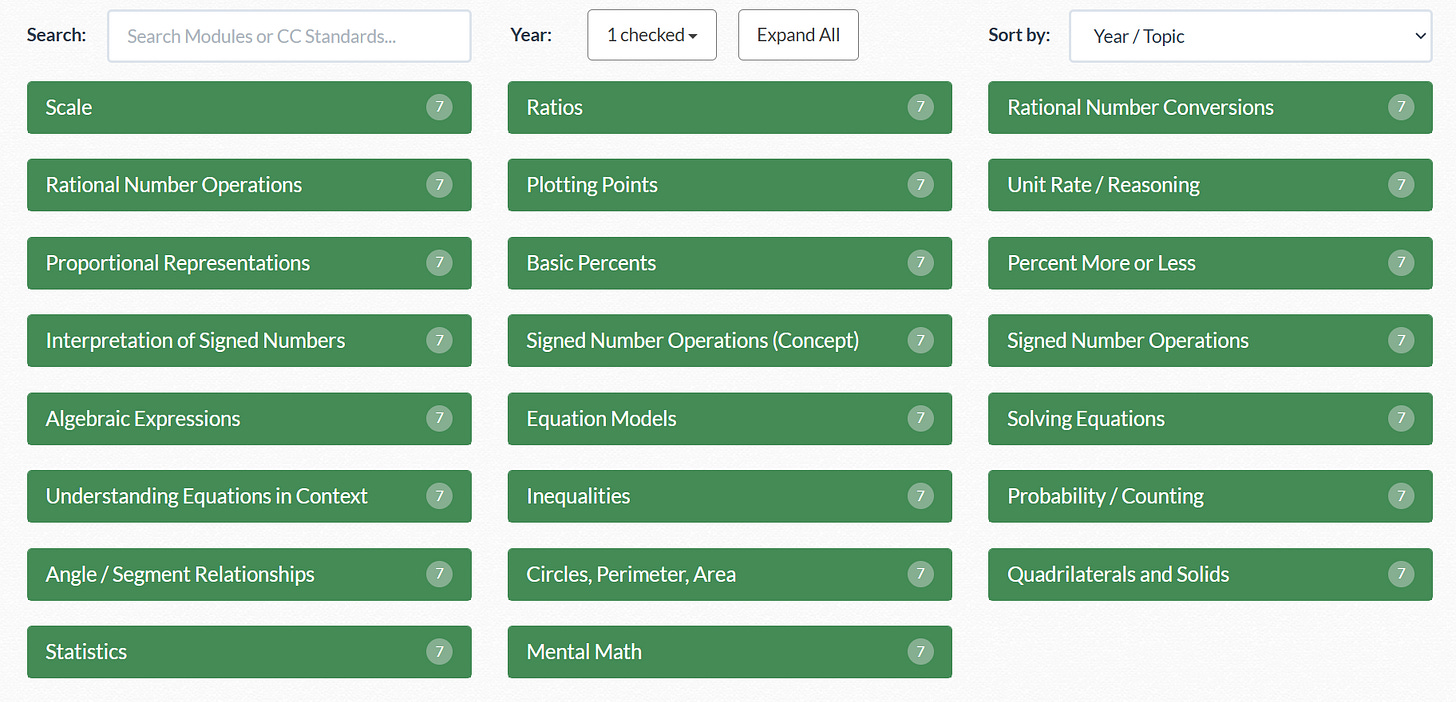

The Only Good Digital Textbook

The heart of Deltamath is an enormous list of skills. There’s unlimited practice for each skill via random numbers plugged into a few question formats. The lists are organized by grade-level and topic.

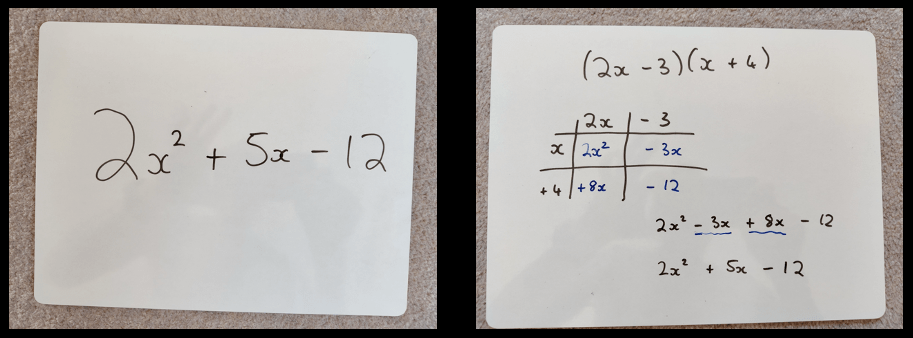

When it’s time for whole-class practice, I’ll hand out personal whiteboards, probably more useful and flexible than any piece of software could ever hope to be.

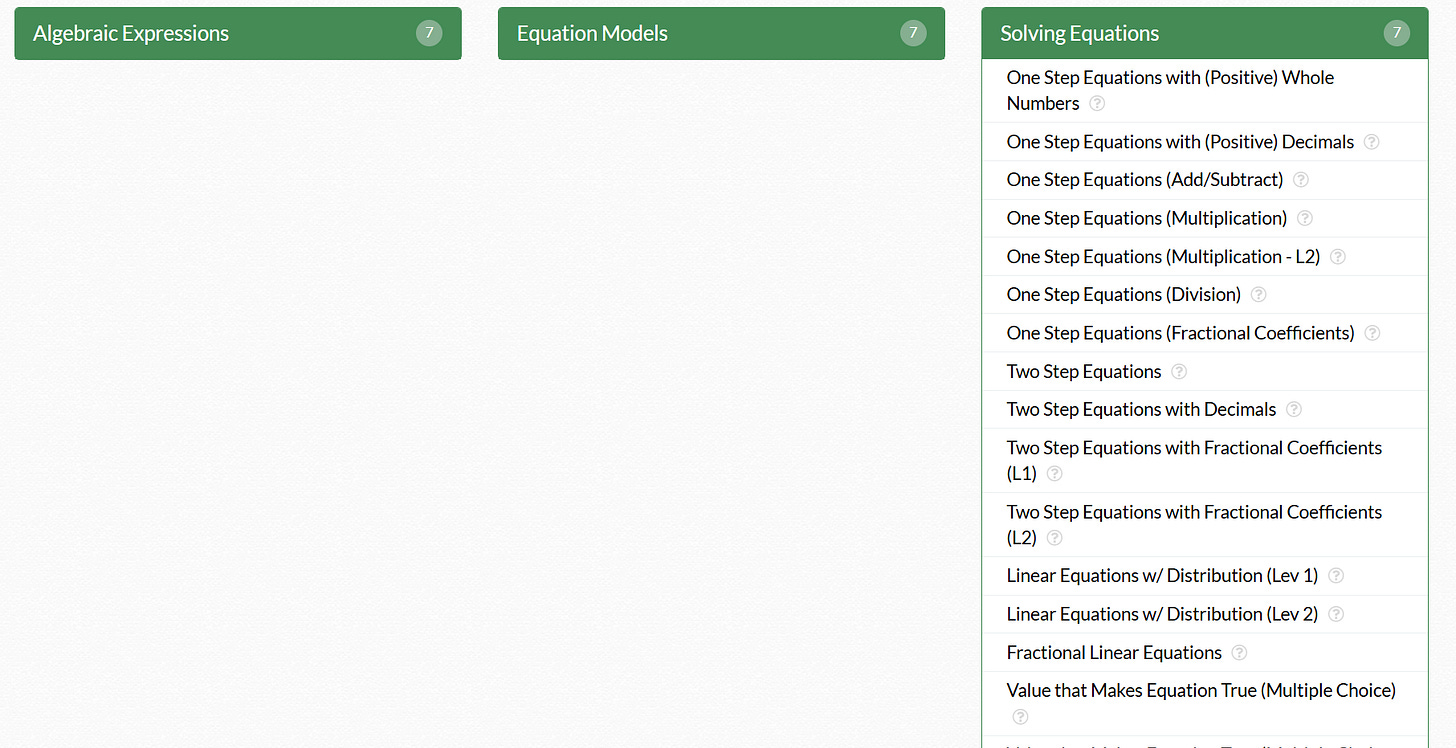

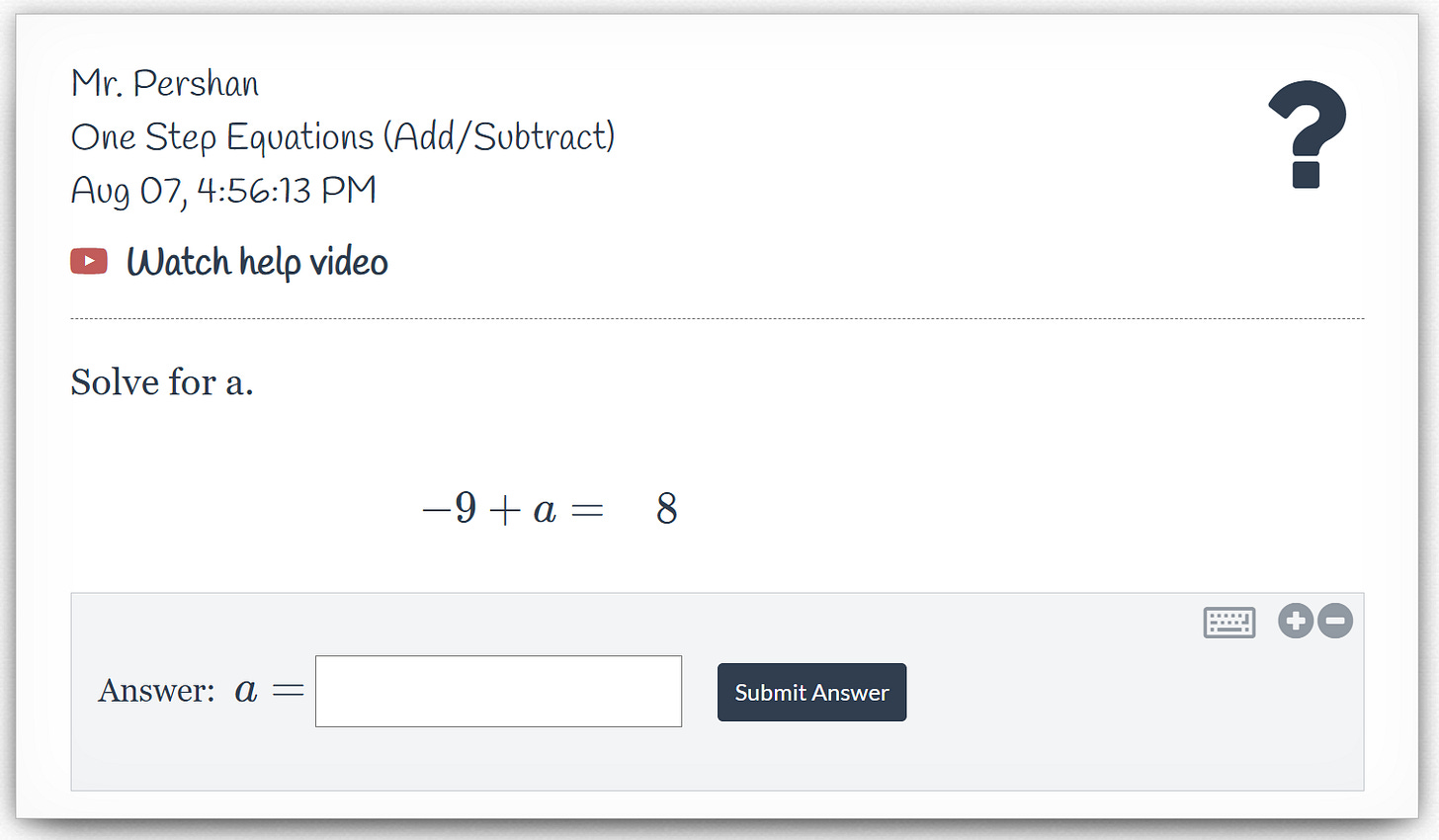

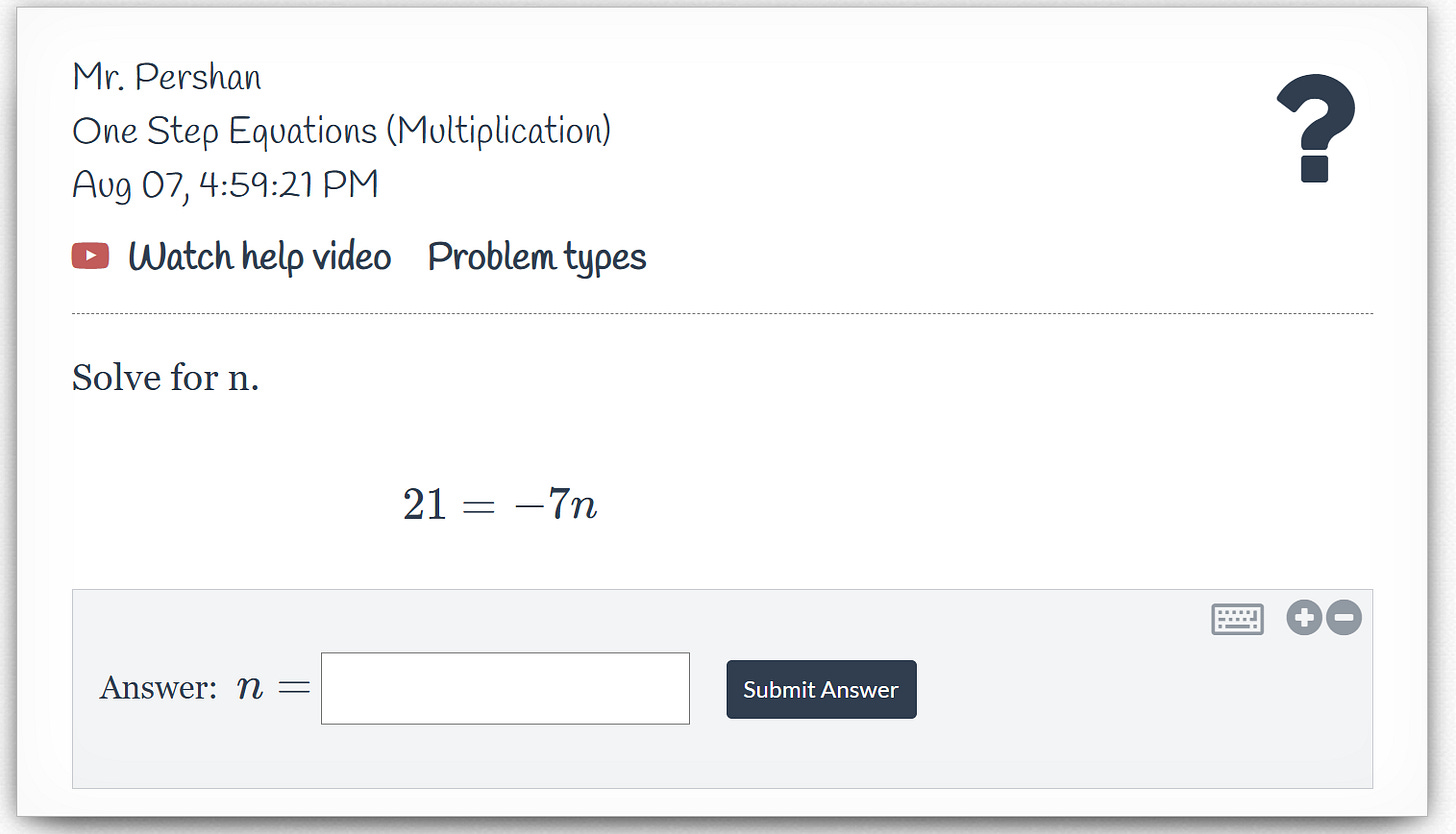

Say that the class is learning to solve equations. I’ll open the “Solving Equations” tab on Deltamath, which exposes an entire sequence of skills.

“I’m going to put a problem on the board,” I’ll say. “I’d like you to solve it on the board. We’ll start with the top of the list and see how far we can go.” I’ll project a simple-ish problem from a skill near the start of the sequence.

“Now lift up your boards,” I’ll say. “That’s pretty good. You all seemed pretty confident. Everybody wipe your boards. Let’s try another one like that.”

Why another one like that? Maybe because one kid got the previous question wrong —I want to give him another shot. Maybe I just want everyone to have a few wins before moving on. I get to decide.

“Let’s turn up the difficulty a little bit.” I’ll project a problem from the next skill and ask everyone to try it.

And so on, exploring the sequence of skills, until I hit friction. I’m probing for where things break down. I want to leave with an understanding of what the class knows and what they need to work on next.

This is dynamic. Depending on how students answer, I’ll change the questions they’re served. Look at me—I’m the algorithm. And I’m getting an enormous amount of information from the kids, though thank god there’s no teacher dashboard. I can see the “data” directly and simply. It guides my instruction. It’s news I can use. (Do we still call this formative assessment?)

More good news: in my experience, it’s all very motivating. Why? I guess it’s because the expectations are clear, the teacher is watching, attention is directed, progress is tangible, feedback is frequent, there’s a bit of competition but everybody’s in on this together. Plus, nobody gets called out for messing up. It’s the class that moves on to the next skill in the sequence. I’m treating the group as a group, even as I’m giving individuals a chance to get on board. (Now compare that to individuals on Chromebooks.)

Could I do this without Deltamath? Absolutely, but it would be harder and worse. I would have to prepare a list of problems in advance. Print textbooks often don’t have many problems for each type of equation. I might make up problems on the spot that are too hard or too easy, especially as the questions get trickier. I might forget a type of problem. I bet you can think of lots of things I’d do wrong — I’m kind of a mess.

To put it differently, there is a quality textbook hidden inside this practice software. And there are a lot of uses for a good digital text. It makes whole-group practice, a winning activity to start with, even better and easier to pull off.

It’s Hard To Use These Things as Intended

My point isn’t to trash individual practice, which is essential for learning anything.

About once a week, I’ll use Deltamath in class for what it was designed for. I could go on about all the little things I do to make it work well, but a lot of that is extremely boring. Like, “hand out paper in advance” levels of boring.

But it’s interesting just how much needs to be done to get this individual learning to work for kids. All the things that those teachers using ALEKS or IXL complain about are real. Kids get stuck easily. When they’re stuck, they might just click around randomly for a while and not ask for help. They might ask their friend to just do it for them. They’ll ask to go to the bathroom. They flirt. Cheat. Open another tab. Try to walk away.

There are ways to handle all these issues. But it’s hard. When I have kids doing practice with those mini whiteboards, I have one big problem to manage; when I hand out computers, I’ve created a few dozen .

And if a district admin or a principal told me that I had to hand out those computers every day and deal with all those little problems on a daily basis, I very well might lose my mind. I’d complain to Holly Korbey. I think, tragically, my classroom might fall victim to an act of vandalism. Something destructive but easily deniable, like a collapsed shelf or a thrown drink. Maybe I’d pay a kid to do it.

It shouldn’t be surprising that practice software is flailing around, complaining that people aren’t using it right. They’re trying to tackle one of the harder parts of teaching, and while I get what they’re going for, their solutions actually make it worse.

Trust me, I’m aware of the problems with whole-group practice. I’ve tried to teach factoring to kids who can’t add. I’ve split a class in two to deal with a huge range of skills. I’ve been interrupted in most of the ways a human being can be interrupted. I know that all ideals fail spectacularly in practice. But personalized learning is the wrong ideal. It’s thinking about this the wrong way. We shouldn’t be going all-in on kids learning on their own. We should be trying to figure out how to make whole-group learning even better.

There’s a great deal of research on peer effects that I’m not deeply familiar with. My impression is that these are potential real, probably not a huge deal, potentially more so for groups of advanced students. Let me know if you know of a good review of peer effects in math. (Here’s a paper to get you started.)

Thanks for sharing. I've never used DeltaMath this way - I write out a list of problems in a progression, but I'm going to consider whether I might want to do this. I would love the boring list of what you do to improve the effectiveness of using DeltaMath in the "traditional" way, including handing out paper.

I find myself really torn here. I'm a huge proponent of peer effects and the power of working together to learn something. I hated IXL when my kids were "learning" on it. I even hated some of the possible better individualized software like Beast Academy online for my kids. Yet I choose to homeschool them. So they kind of get individualized learning that allows them to advance really quickly.

I think many of the practice software programs are the worst of all world. I appreciate you writing this.