Understanding and Habit

Making sense of arguments about teaching

At a certain point last night I needed to know exactly when people started arguing about memorization in learning. A simple search landed me on a New York Times article: “Use of Memorization in Schools Fading.” That’s from 1982, but I knew I could do better.

I continued and traced it back to 1947: “City Schools Are Developing Fresh Techniques to End ‘Monkey-Rote’ Approach.” I then needed to know if “monkey-rote” was a common phrase in 1947. It was not, :-(.

Another click or two and I was all up in an 1893 report by F.E. Marshall, a person that I have no further information about: “I believe that addition and subtraction tables are given in some books to be committed to memory; would that they were committed to the flames.” Intense!

Now here’s grammarian Guarino of Verona in 1425: “I will repeat and repeat again, and recommend many, many times that you must exercise the student’s memory. Give him something to memorize, and pay more attention to repetititon than to explanation.”1

But by the time I worked my way to Quintilian, a 1st-century Roman writer—“our whole education depends upon memory”—I decided I’d had enough, and came back to the present, where things are as confused as ever.

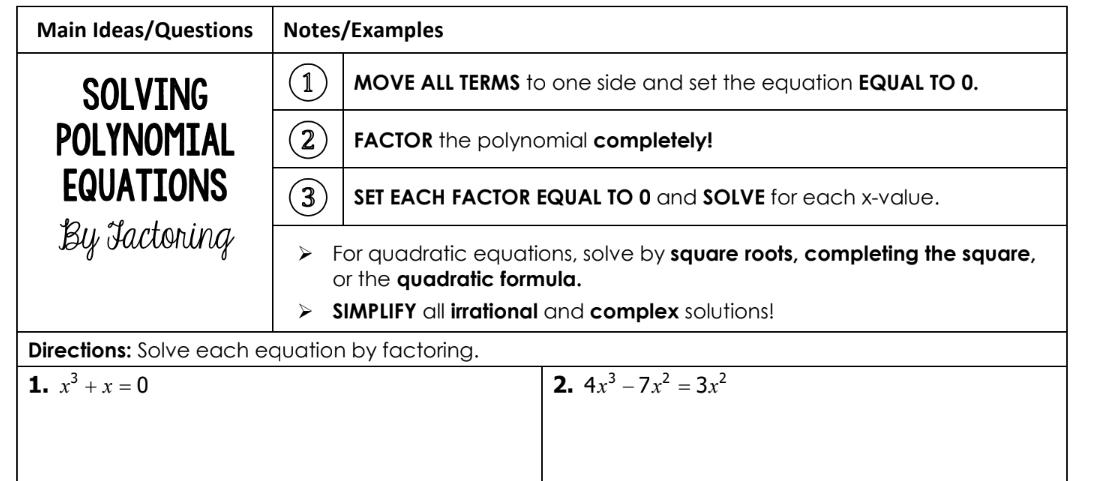

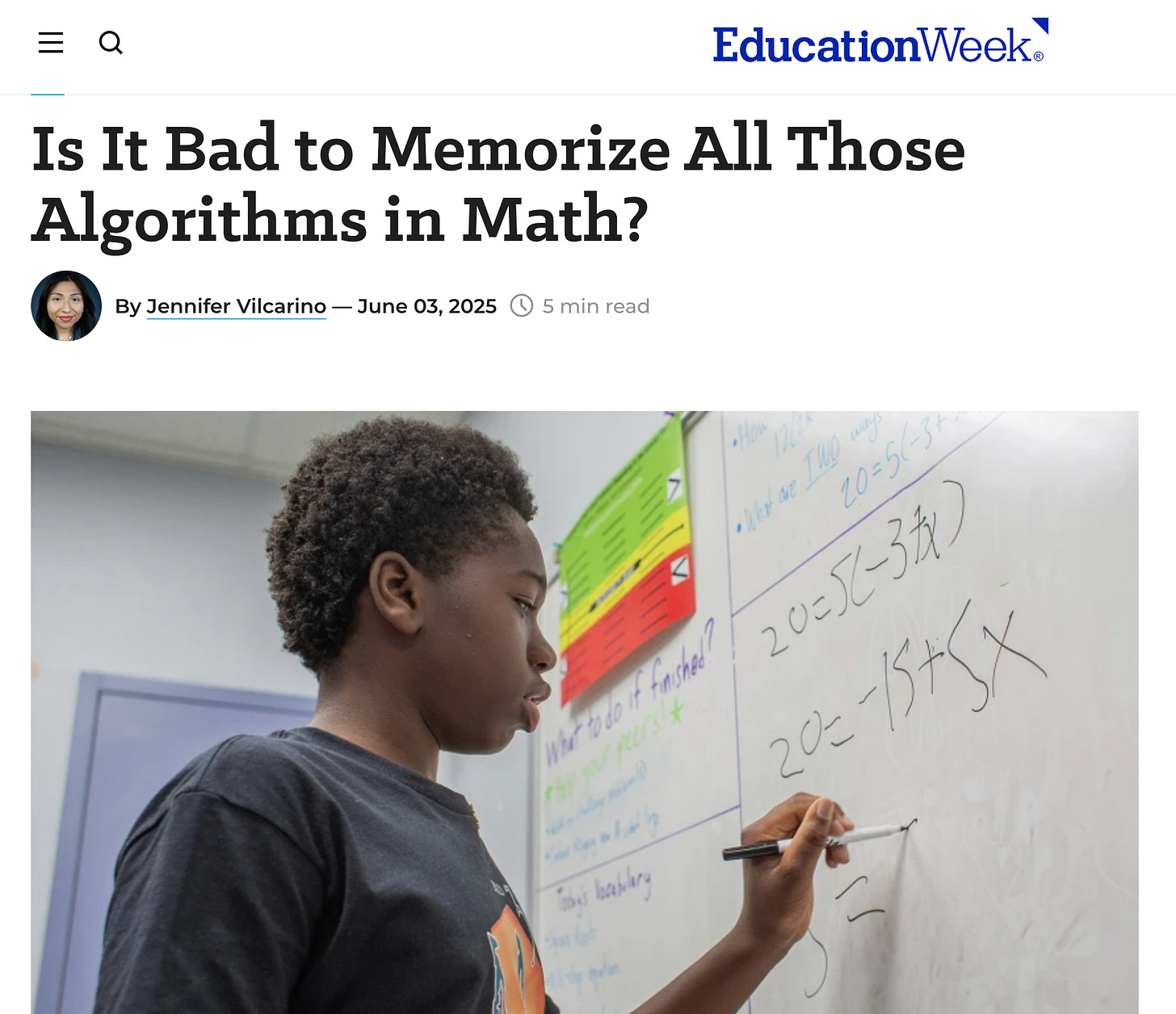

Last summer, Education Week featured Pam Harris, a mathematics teaching consultant, who argued that “too many classrooms focus too much on memorization.” Reporter Jennifer Vilcarino also brought in Bethany Rittle-Johnson, a leading researcher in this area, who said students “need to memorize math facts” in order to “free up their minds to see the more interesting things.”

I’m generally on board with Rittle-Johnson’s way of seeing things. But Harris does have a point: “memorize-the-steps” teaching really does happen, and it’s really not great.

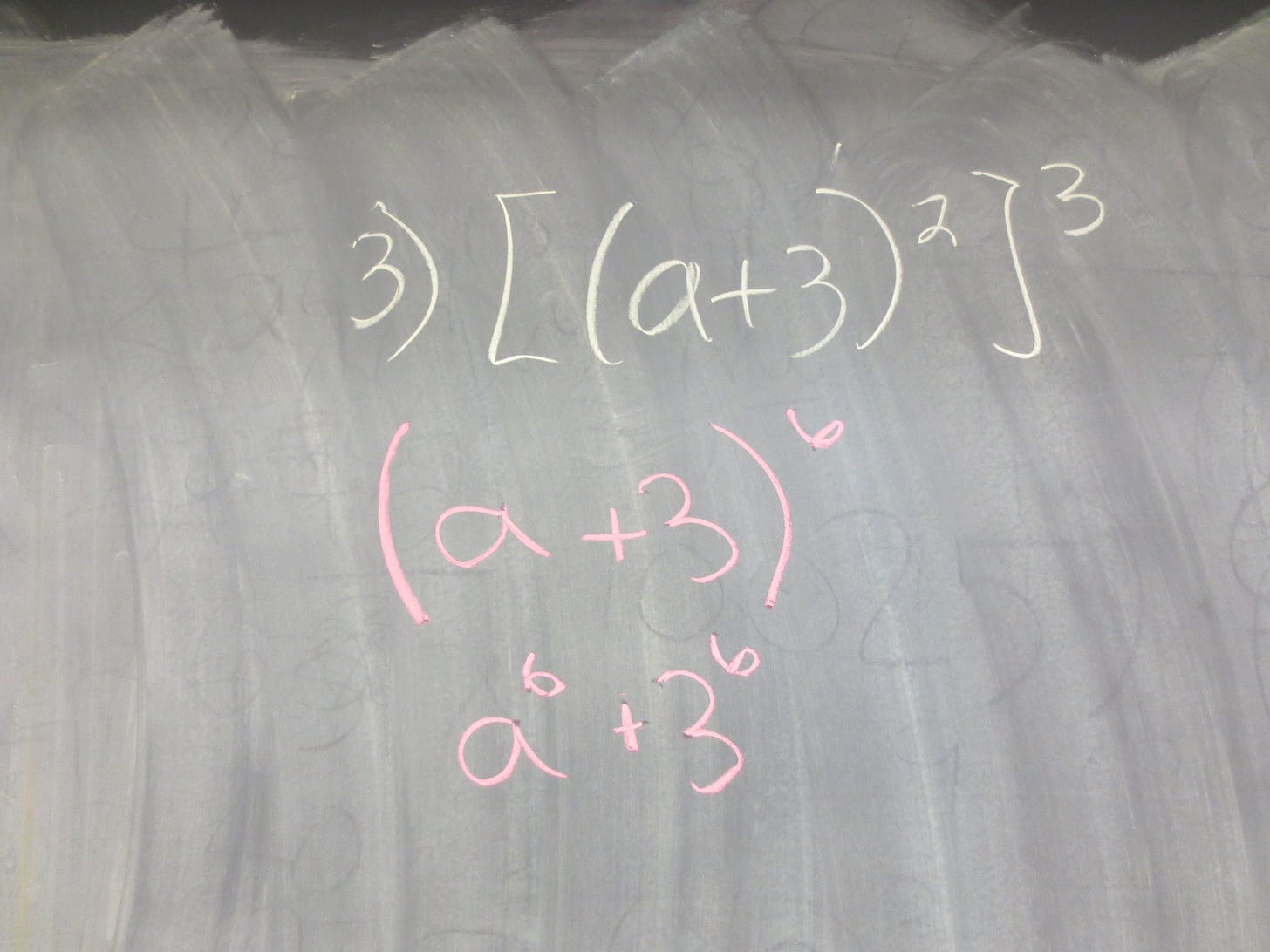

The core problem with “memorize-the-steps” teaching isn’t that it’s boring or that it’s taking away a chance for discovery. The problem is, basically, that it doesn’t work, because even if the knowledge of the steps sticks in your head, that doesn’t necessarily help you become fluent in the procedure.

Explaining why takes us into what I see more and more as the core challenge of education—using language and explicit direction to steer our habits.

People Who Can Only Form Habits

There are people who, due to illness or trauma, are not able to form hold on to new information. Somehow, there are things they can learn, though they have no recollection of the learning experiences.

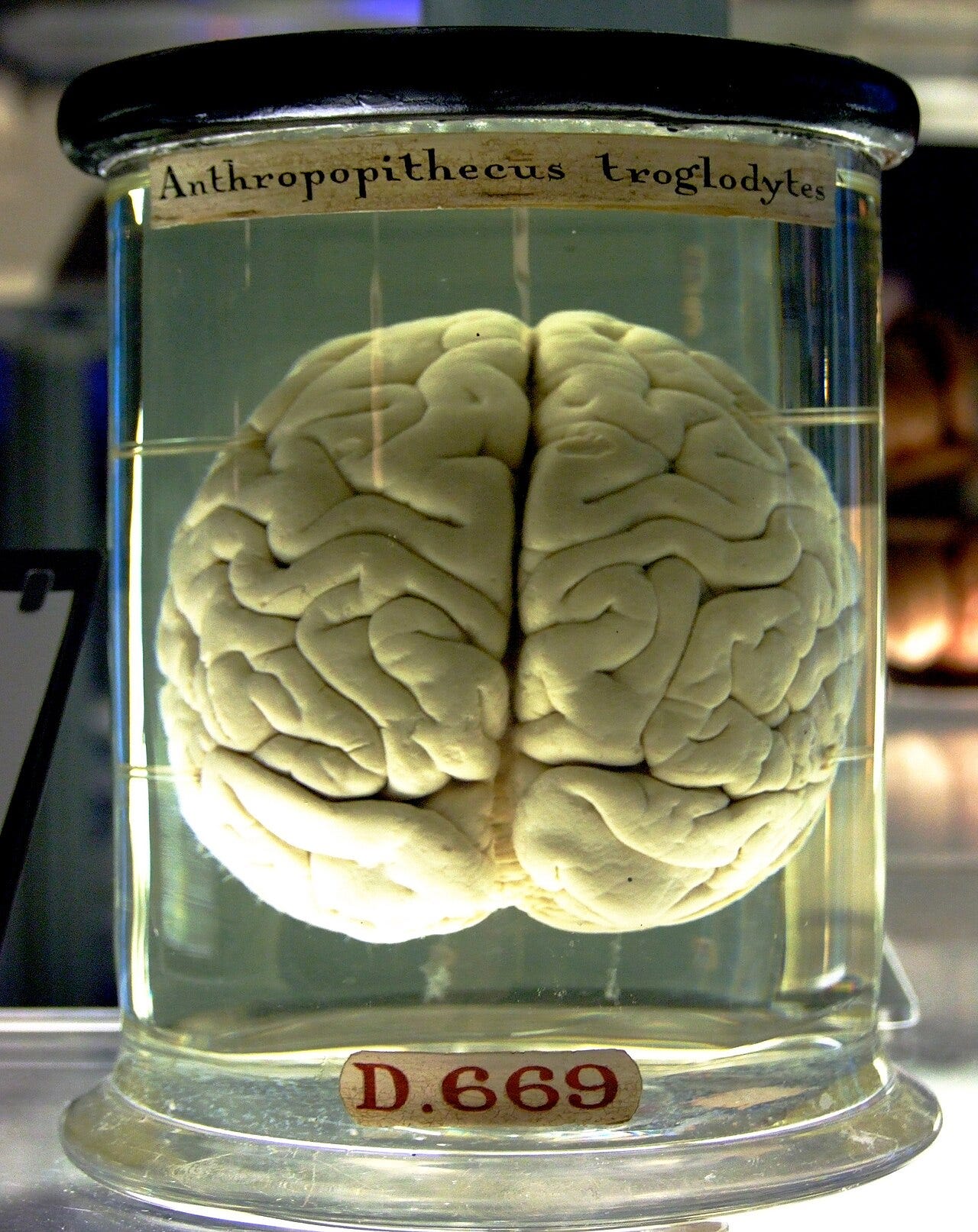

Clive Wearing has a near total loss of short-term memory. He experiences time in several-second episodes. It’s the stuff of literature and nightmares. At 47 years old, married, with children from a previous marriage, Clive Wearing contracted a virus that caused traumatic swelling in his brain: encephalitis. He was not expected to survive. When he did recover his brain was damaged. As a result he can not remember what he does, even moments after he does it. If he looks away, he will be surprised by your presence when he turns back. He keeps a diary—a sad, awful, beautiful diary. As a former musicologist and conductor, he was (is?) still able to play the piano, but as lovely and stirring as it is to watch videos of him playing, music providing a modicum of peace and continuity in his otherwise baffling life, let’s not kid ourselves—this shit is harrowing in the extreme.

And yet, there are things that Wearing (now 85) is able to learn. As described in the documentary Living Without Memory:

The interesting thing is that even though on a minute-to-minute basis he is forgetting everything that happens…he does show signs of implicit learning. For example when he’s been watching the same video every day, he now anticipates what is going to happen on the video, though he has no conscious recollection of ever seeing the video before.

This ability to gain new skillful knowledge even as one’s capacity to form new explicit memories has been irreperably blasted was also documented in the most famous case of Henry Molaison, known as H.M., who also suffered from lobotomy-induced amnesia. Yet H.M. was also able to make typical progress on skills like tracing a star while only watching its reflection in a mirror—a difficult task for most of us.

What is going on here? How is this learning possible? The conventional explanation is that this attests to two different systems of memory, fed by two different processes for learning—declarative and procedural.

Declarative memory is supposedly explicit. It’s often represented via language. It’s facts. It’s learning a new word for a new concept. It’s remembering my middle name. It’s knowing a rule, or a technique, a recipe, steps, an event, a story, a setting, an explanation.

Procedural memory, as researchers Knowlton and Shor put it in the Oxford Handbook of Human Memory, is “a form of implicit memory that enables us to perform skills after sufficient practice and experience without necessarily having conscious access to what has been learned.”

Like a lot of these things, the declarative/procedural distinction isn’t absolute, and the two notions seem incredibly entangled in practice.2 There’s probably no skill of any importance that doesn’t require developing both explicit and implicit knowledge. And yet there’s something undeniable about the observation. Clive Wearing can learn skills but not facts, and we all do complex things without thinking about them.

What Everyone Needs to Know About Learning

At the end of a recent class, a student came up to voice a frustration. She felt as if she understood what we were doing in class but couldn’t stop making mistakes. There was no question. It was more of a confession. If she was asking anything, it was something like, What is wrong with me? Am I just bad at this?

The answer is, no—absolutely not. This is the most normal experience ever. It’s the clash between your explicit understanding and your habits.

I told this student about the difference between understanding and forming a habit. The first thing involves focus, explanation, explicit thinking. The second, forming a habit, takes time as we retrain our associations. That sometimes involves untraining previous habits. It’s hard, laborious, and there is no real shortcut.

I see this as connected to Ira Glass’ little rant about taste outpacing ability for beginners:

“Nobody tells this to people who are beginners, I wish someone told me. All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you. A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this.”

Learning a mathematical skill ideally doesn’t take years. But there is something parallel to this in school learning. You can understand how to solve a problem without being able to successfully solve it. Conversely, you can solve problems without necessarily understanding how you solved it.

Math Wars are Over (If You Want It)

In the EdWeek article, critics of memorization are unsure how to think about procedures that have become habitual. Pam Harris seems opposed to automatic, implicit procedural knowledge entirely:

“What we don’t need is to practice algorithms over and over and over, because what that gets us is maybe good at those algorithms. ... In reality, doing math means doing the mental actions that mathematicians do.”

Whereas Latrenda Knighten, of NCTM, seems to express the (correct) position, that the only problem is memorizing procedures, instead of practicing them to the point at which they become fluent:

Knighten differentiated algorithms from memorization by their use. Algorithms allow students to solve problems efficiently, and practicing them ultimately leads to knowing them by heart. But that shouldn’t mean they don’t have a strong grasp of the mathematics underlying the steps.

“Students will memorize something just from over time, but at the same time, they still need to be able to understand what those things mean,” said Knighten.

And Rittle-Johnson is most certainly not proposing that students memorize things that they don’t understand:

“Students should really be generating explanations, trying to make sense of things, and [looking for patterns is] just a set of instructional methods and tools that, in general, can support and connect procedural fluency and conceptual understanding,” said Rittle-Johnson.

I see the issue as basically a mistrust of habit. Harris thinks that mathematicians make every decision explicitly, without relying on instict and mindless procedures—that is not correct, because we form habits and associations from noticing correlations in our experience, without even trying. There is implicit learning for this implicit knowledge.

Meanwhile, teachers who ask students to memorize steps of complex procedures have made the same mistake. They want students, weeks later, to think back and recite mnemonics and memorized steps to solve problems. That’s not what expertise looks like. We practice to the point of fluency because that is much more reliable than laboriously recalling a memorized step and then figuring out how to apply the recipe to the problem at hand. And that is fairly mindless, since so much mental fuel is spent attending to that recipe.

Part of what makes these arguments tedious is that they elide over these basic distinctions. That our minds have these different, somewhat independent capacities is a truly basic fact about humanity—trace it back to Plato’s idea of a divided soul, if you like!

But, on the other hand, I get it. The relationship between explicit and implicit knowledge is, in fact, extremely confusing. Some students seem to be able to quickly take explicit direction and translate it into solid habit. For others, the gap seems wider, and it takes endless practice to train more accurate associations. We don’t always know how to goad the unconscious, fast-acting mind into more productive habits.

And that’s not just about teaching.

A person knows they should stop smoking but just can’t quit. A child loves museums, but gets anxious about the trip anyway. We resolve to give more to charity but don’t follow through. We promise to stop doing that thing that drives our spouse crazy, but after a month of conscious effort, we fall into old ways. We have this knowledge and understanding, and we want to impose it on ourselves, but our habits—often invisible in the moment—guide us differently.

In other words, what’s most confusing about teaching is what’s most confusing about being a person: how to get a handle on our instincts and steer them in the right direction. If you want to learn or change, there’s no way to avoid engaging with the invisible, ‘mindless’ stuff; but it’s not necessarily going to be easy, so I get why you’d want to try.

From “Schooling in Renaissance Italy” by Paul F. Grendler. Not exactly a fun read.

Here’s researcher Arnold L. Glass: “It is clear that learning to walk is procedural, but what is learning to talk? Recognizing words is clearly declarative, but what is organizing them into novel, grammatical sentences—procedural or declarative? Athletic skills appear procedural, but what are math skills? Presumably, learning the numbers and simple addition is declarative. Does addition become procedural when a math problem is solved, even though the individual is a applying a declarative rule that has been learned? With practice, does math knowledge become procedural as well as declarative?” You can do this all day.

I'm not a math teacher, so please correct me if I'm wrong, but wasn't this the whole point of the much hated "New Math?" Wasn't the goal not just to teach students the steps, but also the theory behind the math, behind the steps. That's my impression. Unfortunately, a combination of poor preparation for teachers, and rejection by parents who "felt stupid when helping their elementary school kids with their homework" put the kibosh on New Math. Am I off base?

We recently had a PD session where the speaker (John Sowash) said that the invention of the written language was deeply resisted by Plato (or was it Socrates?) because it would be the end of memorization and the decline of mankind/society.