Harry writes in with a question:

I am looking to potentially dive deeper into math education research, and, in general, learning research. Is there a good place to go to get a broad, wide eyed overview of this ever growing body of research? Somewhere that maybe categorizes and/or summarizes different branches of the research landscape that would help me get a lay of the land before deciding which individual pieces to explore further?

I think the answer to your question is no, a guide of the sort you’re imagining does not exist—at least not in a way that would satisfy me, if I were in your shoes. And while it’s tempting to encourage you to simply dive in, there is probably something useful to say about the “lay of the land,” as you put it.

But first…it’s incredibly flattering to be asked a question. Thank you, Harry! If anyone else wants to ask me something, don’t be shy, as long as you’re OK with it potentially getting answered in a post like this one. Reply to this email, message me through substack, or get in touch with me on bluesky or twitter.

Back to Harry’s question.

The first issue with research on education is that it belongs to too many fields. Say you’re interested in a controversial topic such as ability grouping and tracking (something I once looked into). You’ll find papers by economists. You’ll find papers from policy researchers. You’ll find things coming from psychological scientists. Then there are education researchers, or even those who identify as math education researchers. You might even catch an historian or two. And wait—how could I forget about special education? And sociologists! And anthropologists!

And it’s not always simple to compare the evidence coming from different fields. Let’s say a lab experiment finds such-and-such, but an observational study finds that it’s not working well in classrooms. Do we say the teacher mismanaged the practice? Or that the lab setting was unrealistic? Imagine further that a law is passed requiring teachers to do such-and-such, and economists find it was actually harmful for learning—how do we square all these results?

A second issue is that these fields are often ideologically polarized. You would be very unlikely to see a mathematics education researcher come down strongly in favor of ability grouping in math. I’d be equally surprised to see an economist or policy analyst come down strongly against it. Why? I guess it might come down to the characteristic lenses and perspectives in these fields, or the biases of the people who go into them. But I think the polarization is, at this point, completely self-sustaining. The fields themselves simply represent opposing perspectives on controversial topics.1

This means that if you only read work coming from one field, you’re sometimes going to get a skewed sense of the issues and the evidence.

Then there is a third issue which is that not all fields study all topics. If you search for “effective ways to memorize multiplication facts” (as I once did) you’re going to find hundreds of studies, almost exclusively from special education researchers. If on the other hand you search for “productive struggle” (another past adventure) you’ll only land on papers coming out of math education—which makes sense, as it’s a phrase invented by math edu researchers. So, depending on how you frame your search, you may end up with papers that reflect only one side of a debate.

To be fair—and I guess I’ll call this the fourth issue—this stuff is inherently complex. You may start off looking for research on how to best assign homework (what is wrong with me) and end up entangled in a whole knot of questions—what age are the students? what’s the subject? what are we trying to measure? how are we trying to measure it? are we measuring the impact of teachers who assign more homework? or time spent by the student on homework? or homework policies that come from the school? or or or or or?

And so, getting back to your question Harry!, the issue is that the only way to understand education research in my view is to read widely across fields. Otherwise you get stuck in a rut. You’ll hear math edu researchers sometimes say things like “we’ve known for fifty years that tracking harms kids!” when generally speaking that is not true at all. And I think special education researchers at times overemphasize just how essential fact memorization is for a typical young student’s development.

So, what does one do?

I don’t know, man. My path was not efficient. I went topic by topic. I got a feel for social psychology by reading a lot about growth mindset. I did a deep dive on cognitive load theory and worked examples and that’s how I learned about cognitive science. For a while I got really into the history of schooling, and actually recently acquired a very dull looking text about abacus schools. And so on. It’s not a bad way to go about things, though it’s admittedly slow, and not really something I’d ever advise any working teacher to do, since we all have other things going on. Still, I don’t regret any of these projects.2

Still: is there a faster, more organized way to proceed?

In an attempt to actually say something useful, let’s try to break things into three big categories:

Psychology & Cognitive Science

Policy & Economics

Education/Math Edu

And let’s take them one at a time. As an amateur I know I might describe these fields in ways that could be a little bit off. Feel free to chime in with an objection!

Psychology & Cognitive Science

First, psychology is a huge and varied field. Carol Dweck is a social psychologist. She studies motivation, emotions, identity, things of that sort. Daniel Willingham is a cognitive psychologist. He studies how the minds learns, reasons, and more generally processes information. Martha Alibali is a cognitive and developmental psychologist with a focus on mathematics—her work on the equality concept is Must See TV for teachers. The late Lynn Fuchs, a special education researcher, studied struggling students and designed interventions.

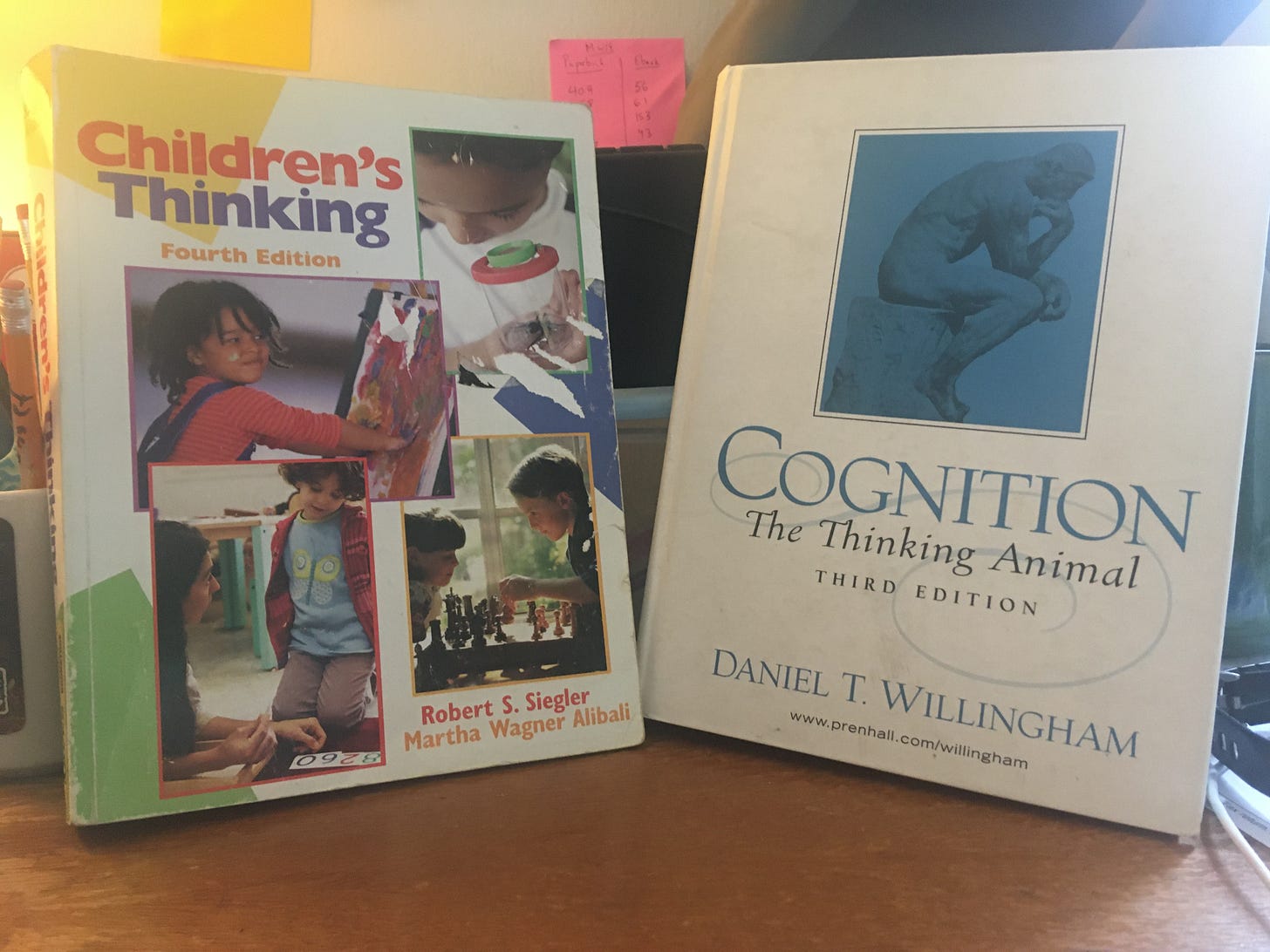

Looking at my shelf, I have two psych textbooks that I value highly: Children’s Thinking by Alibali and Siegler, and Cognition by Willingham. Texts seem like a fine place to start for psych. There’s probably a good social pysch text out there too. At one point I had my hands on Learning Disabilities (Fuchs was a co-author) and liked it. There’s nothing wrong with textbooks—I think at the end of the day I find reading them less interesting than noodling around with papers, but maybe I’m. Just. Built. Different.

Then there are approximately a million books that aim to present cogsci research to practitioners. I wrote one about worked examples. Craig Barton wrote a good one about math teaching, more generally. You could go to Ollie Lovell’s podcast. I recently got a look at a new title by Jim Heal and Rebekah Berlin that looked quite clear—Mental Models. These books all mention worked examples, retrieval practice, spaced repetition. Things like that.

I guess it’s fair to say you’ll get more lab-based experiments than classroom studies in these fields, but that’s definitely not strictly true. (Especially historically. If you go back to the 1960s, cognitive scientists loved the think-aloud protocol, where they’d analyze a transcript of someone talking while working on a task. Nowadays a study like this would more often appear in education research than in cognitive psychology.)

One last little thing, you might check out the What Works Clearinghouse guides to see summaries that reflect the perspectives of these fields.

Policy & Economics

Teaching and learning is full of details and subtlety. But we all want to make generalizations. And that’s what policy is, isn’t it? A big, dumb generalization that we hope does more good than harm.

Take growth mindset. Whether a growth mindset intervention “works” or whatever is a question for social psychology…up until the moment when someone tries to make all the kids in a district (or a state, or a country) do an online growth mindset intervention, one that will necessarily be somewhat watered-down. At that point we’re at a scale where such a study leaves the world of psych and instead might be published in a journal called Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis.

Along those lines, there is something new and very useful to share! It’s called LiveHandbook and it does basically what I want every field to do—collect handy little encylopedia-style articles summarizing what is known, topic by topic. I’m impressed so far—they seem to have done this in a reasonably objective way. LiveHandbook is now my go-to stop when I want to learn about charter schools or vouchers or teacher pay or any of the hot topics that non-teachers often care deeply about, instead of the weird little corners of pedagogy that I’ve often obsessed over in my own work.

(LiveHandbook supplements but does not replace my older method, which is looking for what reporter Matt Barnum has to say.)

I’m not especially knowledgable about policy, but I don’t think you’d want to start with textbooks. By its nature, this is education research of the broadest possible interest, so there are book books on every conceivable topic that will be reasonably accessible. (Example: college admissions.)

Eventually you’ll decide that you want to understand more about particular statistical and econometric methods, or you’ll do what I usually do, which is treat them as a sort of mystery math box that hopefully someone out there has checked. The important thing is to not trick yourself into thinking you understand things that you don’t, and to move cautiously in those cases.

One last little thing: you might want to keep an eye on the Annenberg Institute’s EdWorkingPapers site, which posts free preprints of new policy research.

Education & Math Education Research

I once owned a ridiculous two-volume collection of essays called “A History of School Mathematics.” They were so large! I gave them away. One of the chapters (which I no longer have access to) told how math education became a research field of its own. There were many factors, but chief among them was a desire to move beyond experimental and statistical methods. They wanted to deeply observe students and teachers using the tools of anthropology and sociology. (I remember the first time I heard the name Jean Lave.) So math edu research begins with a self-conscious move away from various psychological fields. This chapter, if I recall, ended with a lament along the lines of, “It’s all worked out fine, but I do wish I’d hear about an experiment every now and then.”

Education research is a tricky thing to make generalizations about. It’s partly a matter of professional identity—this is education research because these are professors of education. But there are a lot of professors of education! Some don’t publish a great deal in journals, as their positions emphasize teaching, and they don’t have time or the funds needed to perform major studies. They’ll often describe small-scale efforts involving current or prospective teachers. (Peter Liljedahl comes to mind.) Others work in fancier departments and have a team of graduate students who help them pursue major grants.

I’ll avoid making further generalizations. Education research encompasses a ton, and it’s plagued by what you might call a huge range of seriousness. Some papers do little more than report on a consensus. (See my piece: “Lots of Research, No Evidence.”) But I feel uneasy with the disdain some people have for education research, a dynamic that arguably goes back to the very beginnings of the field. So, I’ll say no more, except that it’s relatively easy to find teacher-friendly information from organizations like NCTM or NCTE, though these organizations certainly have their own ideological perspectives. If you want more, you could poke around the AERA website.

So! There is plenty to read. And at the risk of going on and on, I have one last thing to say about how to read it.

At the very least, no matter how weak the evidence presented is, every published paper is an opinion. Now, sometimes when I meet a person with an opinion, I don’t really care. I just move on. But if someone has a personal experience, and I trust that what they’re saying really did happen, I can learn something from it—even if I disagree with their interpretation. “Oh sure, I don’t doubt that her kids enjoyed that game. Not sure if they learned much from it, but still.” Or whatever.

I like to read all papers in this way. Certainly observational studies. Even experiments are someone’s take on a experience that they themselves designed. “We put kids in a room and gave some of them this problem. We gave other kids this one. And kids learned more from this one. And here’s what we think happened.” Data analysis too—here’s what we saw, here’s what we think. You can learn from what they saw, and decide on your own what you think.

Reading this back, I’m like, duh. Obviously.

But I find it’s helpful to keep the human side in mind. Reading research is just reading. Writing research is just writing. It’s easy to get lost in the language of objectivity. But these are people just telling you what they think. On the one hand, you have to figure out how to put the chorus of voices together, and figure out what parts of what they’re saying you trust and believe. On the other, you have to decide, before dismissing someone entirely, why they aren’t worth listening to. Let’s say they were right here in front of you, telling you what they thought—would you trust them? (Often there’s a good reason not to!)

But ultimately I think it’s good that education is studied across different fields. You should read widely though there will be disagreement and confusion along the way. It would honestly be more concerning if there weren’t.

It’s pretty common for people, either in or out of academia, to just dismiss a bunch of these fields as essentially valueless. Forgetting whether that’s true or not, I have found it useful as a reader to treat all these subfields as expressing interesting viewpoints that are worth taking seriously.

Another thing I did was talk with researchers on social media, mostly twitter, at times putting my foot in my mouth and often baiting people into correcting and teaching me. I’d say this was humiliating but effective, I hope? In the early years, I really owe Ilana Horn in particular a tremendous amount of gratitude for interacting generously and seriously with me. I learned so much about math education research from her and others. With the decline of social media I don’t really know if this sort of education-by-interaction is still a possibility.

Michael,

The perspective you advise is so wise.

I usually look for the nugget of insight that animated the author and find it valuable even when I disagree with their conclusions. The authors are often distracted by their own agenda, but as readers we don’t have to be distracted by it.

When trying to learn, the glow of reading something that validates my pre-existing views is just as blinding as the glare as an agenda I oppose.

Always learn something from you.

A very interesting post, thanks. I appreciate your take on complexity and the need for a multi-perspective approach as well as the fact that you stress the collective dimension of learning in a class as being not a drawback but rather an essential feature. I have decided to embrace this too, holding some resistance against the current paradigm of taylor-made learning.

I would like to add the observation that didactics research in mathematics has very different accents in different countries, and it might be worth seeing what other regions of the world have produced. I teach in Germany and am less than enthusiastic about current German literature, although there is a great tradition like Mathilde Vaerting, Hans Freudenthal, Martin Wagenschein (more a physicist). Some Italians like Rosetta Zan and Bruno D'Amore do very interesting stuff. I learned of Carol Dweck through Jo Boaler, I know she was much criticized but I took many good ideas from her. Well, whatever, thanks, I'll keep on reading.